إمي نوتر

إمي نوتر | |

|---|---|

Emmy Noether | |

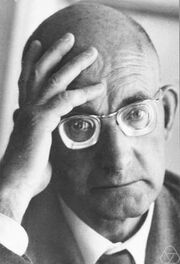

نوتر ح. 1900–1910 | |

| وُلِدَ | أمالي إمي نوتر 23 مارس 1882 |

| توفي | 14 أبريل 1935 (aged 53) برين ماور، پنسلڤانيا، الولايات المتحدة |

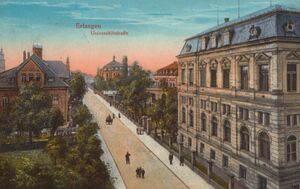

| المدرسة الأم | جامعة إرلانگن–نورمبرگ (دكتوراه) جامعة گوتنگن (التأهيل الجامعي) |

| عـُرِف بـ | |

| الجوائز | جائزة آكرمان–توبنر التذكارية (1932) |

| السيرة العلمية | |

| المجالات | الرياضيات والفيزياء |

| الهيئات | |

| أطروحة | Über die Bildung des Formensystems der ternären biquadratischen Form (حول النظم التامة للمتغيرات للأنماط التربيعية الرباعية الثلاثية) (1907) |

| المشرف على الدكتوراه | پول گوردان |

| طلاب الدكتوراه | |

أمالي إمي نوتر[أ][ب] (23 مارس 1882 – 14 أبريل 1935) كانت عالمة رياضيات ألمانية قدّمت إسهامات مهمة في الجبر المجرد. كما أثبتت المبرهنة الأولى لنوتر ومبرهنة نوتر الثانية، اللتين تُعدّان أساسيتين في الفيزياء الرياضية.[4] وصفها پاڤل ألكسندروف، ألبرت أينشتاين، جان ديدونيه، هرمان ڤايل، ونوربرت ڤينر بأنها أهم امرأة في تاريخ الرياضيات.[5][6][7] وباعتبارها من أبرز علماء الرياضيات في عصرها، طوّرت نظريات الحلقات والحقول والجبر. وفي الفيزياء، تفسر مبرهنة نوتر العلاقة بين التناظر وقوانين الحفظ.[8] وُلدت نوتر في أسرة يهودية بمدينة إرلانگن في فرانكونيا؛ وكان والدها عالم الرياضيات ماكس نوتر. في البداية خططت لتدريس الفرنسية والإنجليزية بعد اجتيازها الامتحانات المطلوبة، لكنها اختارت بدلاً من ذلك دراسة الرياضيات في جامعة إرلانگن–نورمبرگ، حيث كان والدها يُدرّس. بعد أن أنهت درجة الدكتوراه عام 1907 تحت إشراف پول گوردان، عملت في معهد الرياضيات في إرلانگن بلا أجر لمدة سبع سنوات.[9] في ذلك الوقت كانت النساء مستبعدات إلى حد كبير من المناصب الأكاديمية. في عام 1915 دعاها داڤيد هيلبرت وفيليكس كلاين للانضمام إلى قسم الرياضيات في جامعة گوتنگن، أحد أبرز المراكز البحثية الرياضية في العالم. لكن كلية الفلسفة اعترضت، فكانت تلقي المحاضرات أربع سنوات باسم هيلبرت. وقد مُنح تأهيلها الجامعي عام 1919، مما أتاح لها الحصول على رتبة Privatdozent.[9]

ظلت نوتر عضواً بارزاً في قسم الرياضيات بگوتنگن حتى عام 1933؛ وكان طلابها يُعرفون أحياناً باسم "أولاد نوتر". في عام 1924 انضم عالم الرياضيات الهولندي بارتِل ليفن ڤان در ڤاردن إلى دائرتها العلمية، وسرعان ما أصبح المفسر الرئيس لأفكارها؛ إذ استند المجلد الثاني من كتابه المؤثر الجبر الحديث (1931) على عملها. وبحلول وقت محاضرتها العامة في المؤتمر الدولي لعلماء الرياضيات عام 1932 في زيورخ، كانت مكانتها في الجبر معروفة عالمياً. وفي العام التالي، أقصى النظام النازي في ألمانيا اليهود من المناصب الجامعية، فانتقلت نوتر إلى الولايات المتحدة حيث تولّت منصباً في كلية برين ماور بپنسلڤانيا. هناك درّست لطالبات الدراسات العليا وما بعد الدكتوراه، منهن ماري يوهانا ڤايس وأولگا توساكي–تود. وفي الوقت ذاته ألقت محاضرات وأجرت أبحاثاً في معهد الدراسات المتقدمة بپرنستون، نيوجرزي.[9]

يُقسم عمل نوتر الرياضي إلى ثلاث "عصور".[10] في المرحلة الأولى (1908–1919) أسهمت في نظريات الثوابت الجبرية وحقول الأعداد. وقد اعتُبر عملها على الثوابت التفاضلية في حساب التغييرات، أي مبرهنة نوتر، "واحدة من أهم المبرهنات الرياضية التي أُثبتت على الإطلاق في توجيه تطور الفيزياء الحديثة".[11] وفي المرحلة الثانية (1920–1926) بدأت عملاً "غيّر وجه الجبر المجرد".[12] ففي ورقتها الكلاسيكية عام 1921 Idealtheorie in Ringbereichen (نظرية المثاليّات في مجالات الحلقات)، طوّرت نوتر نظرية المثاليّات في الحلقات التبادلية إلى أداة ذات تطبيقات واسعة. وقد استخدمت بمهارة شرط السلسلة الصاعدة، وأُطلق اسم نوترية على البنى التي تحقق هذا الشرط تكريماً لها. وفي المرحلة الثالثة (1927–1935) نشرت أعمالاً في الجبر غير التبادلي والأعداد الفوقية، ووحّدت نظرية التمثيل لـالزُمر مع نظرية الوحدات والمثاليّات. وبالإضافة إلى منشوراتها الخاصة، كانت نوتر سخية في أفكارها، ويُنسب إليها الفضل في عدة اتجاهات بحثية نشرها رياضيون آخرون، حتى في ميادين بعيدة عن مجالها الرئيس مثل الطوبولوجيا الجبرية.

السيرة

النشأة

وُلدت أمالي إمي نوتر في 23 مارس 1882 في إرلانگن، باڤاريا.[13] وكانت البِكر من بين أربعة أبناء لعالم الرياضيات ماكس نوتر وإيدا أمالي كوفمان، وكلاهما من عائلات يهودية ثرية تعمل في التجارة.[14] كان اسمها الأول "أمالي"، لكنها بدأت باستخدام اسمها الأوسط منذ صغرها، واستمرت على ذلك في حياتها الراشدة وأعمالها المنشورة.[ب]

في طفولتها لم تُظهر نوتر تفوقاً أكاديمياً لافتاً، لكنها عُرفت بذكائها ولطفها. كانت قَصيرة البصر وتعاني من لُثغة طفيفة في الكلام. وقد روى أحد أصدقاء العائلة لاحقاً قصة عن سرعة حلها للغز منطقي في حفلة للأطفال، ما أبرز موهبتها المبكرة في التفكير المنطقي.[15] تعلمت الطبخ والتنظيف كما كان سائداً للفتيات آنذاك، وأخذت دروساً في البيانو، لكنها لم تُبدِ شغفاً بأيٍّ منها، بينما كانت تحب الرقص.[16]

كان لنوتر ثلاثة إخوة أصغر منها. وُلد البكر، ألفريد نوتر، عام 1883 وحصل على الدكتوراه في الكيمياء من إرلانگن عام 1909، لكنه توفي بعد تسع سنوات.[17] أما فريتز نوتر فقد وُلد عام 1884، ودرس في ميونخ وأسهم في الرياضيات التطبيقية.[18] ويُعتقد أنه أُعدم في الاتحاد السوفيتي عام 1941 أثناء الحرب العالمية الثانية.[19] أما الأصغر، گوستاف روبرت نوتر، فولد عام 1889، وتُوفي عام 1928 بعد معاناة طويلة مع المرض المزمن.[20][21]

التعليم

أظهرت نوتر بواكير تفوقها في الفرنسية والإنجليزية. ففي مطلع عام 1900 اجتازت امتحان تدريس هاتين اللغتين بدرجة sehr gut (جيد جداً). وقد خوّلها ذلك للتدريس في مدارس البنات، لكنها فضّلت مواصلة دراستها في جامعة إرلانگن–نورمبرگ،[22] حيث كان والدها أستاذاً.[23]

كان ذلك قراراً غير تقليدي؛ إذ أعلن مجلس الجامعة قبل عامين أن التعليم المختلط "سيُطيح بكل النظام الأكاديمي".[24] وكانت واحدة من امرأتين فقط ضمن 986 طالباً، ولم يُسمح لها إلا بالمستمعة الحرة مع ضرورة الحصول على إذن خاص من الأساتذة. رغم هذه العوائق، اجتازت في 14 يوليو 1903 امتحان التخرّج في Realgymnasium بـنورمبرغ.[22][25][26]

في فصل الشتاء الدراسي 1903–1904 درست في جامعة گوتنگن، حيث حضرت محاضرات الفلكي كارل شوارتسشيلد والرياضيين هرمان منكوفسكي، أوتو بلومنثال، فيليكس كلاين، وداڤيد هيلبرت.[27]

في عام 1903 أُزيلت القيود على التحاق النساء الكامل بالجامعات البافارية.[28] عادت نوتر إلى إرلانگن والتحقت رسمياً بالجامعة في أكتوبر 1904 لتتفرغ لدراسة الرياضيات. وكانت واحدة من ست نساء فقط في دفعتها (بينهن اثنتان مستمعتان)، والوحيدة في تخصصها.[29] تحت إشراف پول گوردان، كتبت أطروحتها Über die Bildung des Formensystems der ternären biquadratischen Form (حول النظم الكاملة للثوابت في الأشكال الثلاثية من الدرجة الرابعة)[30] سنة 1907، وتخرجت summa cum laude (بأعلى الامتياز) في نهاية ذلك العام.[31] كان گوردان من مدرسة "الحساب" في دراسة الثوابت، وقد أنهت أطروحتها بقائمة تضم أكثر من 300 ثابت مُفصَّل. لاحقاً حلّت الطريقة الأكثر تجريداً وعمومية التي ابتكرها هيلبرت محل هذا النهج.[32][33] وقد لقي عملها استحساناً، لكنها وصفت أطروحتها وبعض أعمالها اللاحقة المماثلة لاحقاً بأنها "تفاهات". أما أبحاثها التالية فجاءت في مجال مختلف كلياً.[33][34]

جامعة إرلانگن–نورمبرگ

من 1908 حتى 1915 درّست نوتر في معهد الرياضيات بجامعة إرلانگن بلا أجر، وكانت أحياناً تُدرّس مكان والدها حين يعجز عن إلقاء المحاضرات.[35] كما انضمت عام 1908 إلى Circolo Matematico di Palermo وفي 1909 إلى جمعية الرياضيين الألمان.[36] في عامي 1910 و1911 نشرت امتداداً لعمل أطروحتها من ثلاثة متغيرات إلى n متغيرات.[37]

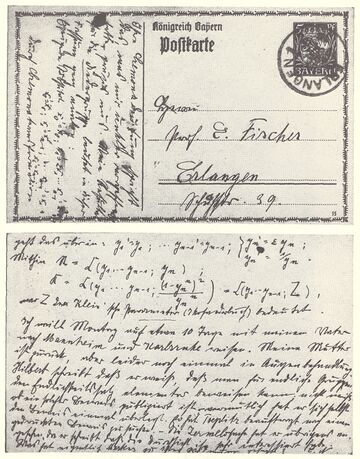

تقاعد گوردان عام 1910،[38] وخلفه إرهارد شميت ثم إرنست فيشر في 1911.[39] وكان فيشر مؤثراً مهماً على نوتر، إذ عرّفها بأعمال داڤيد هيلبرت.[40][41] وقد جمعتها به علاقة علمية نشطة؛ إذ كانت ترسل له بطاقات بريدية تواصل فيها أفكارها.[42][43]

من 1913 حتى 1916 نشرت نوتر عدة أوراق امتدت وطبّقت أساليب هيلبرت على موضوعات رياضية مثل حقول الدوال النسبية ونظرية الثوابت في الزُمر المنتهية.[44] وقد مثّل ذلك أول احتكاك لها بـالجبر المجرد، المجال الذي ستُحدث فيه لاحقاً ثورة.[45]

في إرلانگن، أشرفت نوتر على اثنين من طلبة الدكتوراه:[46] هانس فالكنبرغ وفريتز زايدلمن، واللذان ناقشا أطروحاتهما عامي 1911 و1916.[47][48] ورغم دور نوتر الكبير، كان الإشراف رسمياً تحت اسم والدها. بعد نيله الدكتوراه، عمل فالكنبرغ في براونشڤايگ وكونيجسبرج قبل أن يُصبح أستاذاً في جامعة گيسن،[49] بينما أصبح زايدلمن أستاذاً في ميونخ.[46]

جامعة گوتنگن

التأهل ومبرهنة نوتر

في مطلع عام 1915، وُجهت دعوة إلى إمي نوتر من قِبَل دافيد هلبرت وفيليكس كلاين للعودة إلى جامعة گوتنگن. غير أن مساعيهم لتعيينها جوبهت برفض من قِبَل بعض أعضاء الكلية الفلسفية، وبخاصة من الفيلولوجيين والمؤرخين، الذين أصرّوا على أنّ النساء لا ينبغي أن يصبحن برايفات دوزِنتن. وفي اجتماع مشترك للقسم، اعترض أحد الأساتذة قائلاً: «ماذا سيظن جنودنا عندما يعودون إلى الجامعة ويُطلب منهم أن يتعلموا على يد امرأة؟».[50][51] أما هلبرت، فكان مقتنعاً بأن مؤهلات نوتر هي الأمر الوحيد الذي ينبغي النظر إليه، معتبراً أن جنسها لا أهمية له، فاعترض بشدة على هذا التمييز. ورغم أن كلماته الدقيقة لم تُحفظ، فقد نُسب إليه قوله إن «الجامعة ليست حمّاماً عمومياً»[52][53][54][55]. ووفقاً لما رواه بافل ألكسندروف لاحقاً، فإن معارضة بعض الأساتذة لم تكن قائمة على التحيّز ضد المرأة فحسب، بل شملت أيضاً مواقفهم المناهضة لانتماء نوتر إلى اليهودية وأفكارها الاجتماعية الديمقراطية.[56]

غادرت نوتر إلى گوتنگن في أواخر أبريل 1915، وبعد أسبوعين توفيت والدتها فجأة في إرلانغن. وكانت قد تلقت علاجاً سابقاً لمشكلة في العين، لكن طبيعتها وصلتها بوفاتها غير معروفة. في تلك الفترة أيضاً، تقاعد والدها وانضم شقيقها إلى الجيش الألماني للمشاركة في الحرب العالمية الأولى. عادت نوتر لعدة أسابيع إلى إرلانغن للعناية بوالدها المسن.[57]

خلال سنواتها الأولى في گوتنگن لم تكن تملك منصباً رسمياً ولم تتقاضَ أجراً. وكانت محاضراتها تُعلن أحياناً تحت اسم هلبرت، بينما تؤدي هي دور «المساعدة».[58]

وسرعان ما أثبتت قدراتها عبر صياغة مبرهنة نوتر، التي تُظهر أن لكل تناظر تفاضلي لنظام فيزيائي قانون حفظٍ مقابل. وقد عُرضت ورقتها العلمية بعنوان مسائل تغايرية غير متغيرة (Invariante Variationsprobleme) في 26 يوليو 1918 أمام الجمعية الملكية للعلوم في گوتنگن بواسطة زميلها فيليكس كلاين، إذ لم يكن يُسمح لها بتقديمها بنفسها لكونها ليست عضواً في الجمعية.[59][60][61] ويرى الفيزيائيان الأمريكيان ليون ليدرمان وكريستوفر هيل أن مبرهنة نوتر «إحدى أهم المبرهنات الرياضية على الإطلاق في توجيه تطور الفيزياء الحديثة، وربما تضاهي في مكانتها مبرهنة فيثاغورس».[62]

مع نهاية الحرب العالمية الأولى، جاءت الثورة الألمانية بتغير كبير في المواقف الاجتماعية، بما في ذلك المزيد من الحقوق للنساء. وفي عام 1919 سمحت جامعة گوتنگن لنوتر بالمضي في إجراءات الهبيليتاتسيون (الأهلية للتثبيت الأكاديمي). جرى امتحانها الشفوي في أواخر مايو، وألقت محاضرة التأهيل بنجاح في يونيو 1919.[63] وهكذا أصبحت برايفات دوزِنت (محاضِرة خاصة)،[64] وقدمت في فصل الخريف الدراسي أول محاضرات تُدرج باسمها هي شخصياً.[65] مع ذلك، لم تكن تتقاضى أي راتب لقاء عملها.[66]

بعد ثلاث سنوات، تلقت رسالة من أوتو بويليتس، وزير العلوم والفنون والتعليم العام في بروسيا، يمنحها فيها لقب nicht beamteter ausserordentlicher Professor (أستاذة استثنائية غير موظفة رسمياً، أي بلا تثبيت وظيفي، مع حقوق إدارية محدودة).[67] كان ذلك منصب أستاذية "استثنائية" غير مدفوعة الأجر، وليس "الأستاذية العادية" الأعلى مرتبة التي تُعد وظيفة رسمية حكومية. وقد عكس هذا الاعتراف أهمية أعمالها، لكنه لم يوفر لها راتباً بعد. ولم تبدأ نوتر في تقاضي أجر عن محاضراتها إلا بعد تعيينها بعد عام في المنصب الخاص Lehrbeauftragte für Algebra (محاضرة مكلّفة في الجبر).[68][69]

العمل في الجبر المجرد

كان لـ مبرهنة نوتر أثر بالغ في الميكانيكا الكلاسيكية وميكانيكا الكم، إلا أن الرياضيين يتذكرونها أساساً لمساهماتها في الجبر المجرد. كتب ناثان جاكوبسون في مقدمة الأعمال الكاملة لنوتر:

إن تطور الجبر المجرد، الذي يُعَدُّ من أبرز ابتكارات الرياضيات في القرن العشرين، يعود في معظمه إليها — من خلال أبحاثها المنشورة، ومحاضراتها، وتأثيرها الشخصي على معاصريها.[70]

بدأ عمل نوتر في الجبر عام 1920 حين نشرت بالتعاون مع تلميذها فيرنر شمايدلر ورقة بحثية عن نظرية المثاليّات، عرّفا فيها مثالي أيسر ومثالي أيمن في الحلقات.[71]

وفي العام التالي نشرت ورقتها Idealtheorie in Ringbereichen،[72] التي حللت فيها شرط السلسلة الصاعدة فيما يخص المثاليّات، حيث أثبتت مبرهنة لاسكر–نوتر بصيغتها العامة. وصف الجبري المعروف إرفينغ كابلانسكي هذا العمل بأنه "ثوري".[73] وقد أدت هذه النتيجة إلى ظهور مصطلح نوترية لوصف البنى الرياضية التي تحقق شرط السلسلة الصاعدة.[74][75]

في عام 1924 وصل الرياضي الهولندي الشاب بارتل لندرت فان دير فاردن إلى جامعة گوتنگن. وسرعان ما بدأ العمل مع نوتر، التي وفرت له أساليب بالغة القيمة في التجريد المفهومي. وقد صرّح لاحقاً بأن أصالتها كانت "مطلقة ولا تُقارَن".[76] وبعد عودته إلى أمستردام ألّف كتاب Moderne Algebra في مجلدين، يُعَدُّ من أهم المراجع في هذا الحقل؛ إذ استند المجلد الثاني، الصادر عام 1931، بكثافة إلى أعمال نوتر.[77] لم تكن نوتر تسعى وراء الاعتراف، لكن في الطبعة السابعة أضاف فان دير فاردن إشارة تقول: "مبني جزئياً على محاضرات إ. آرتين وإ. نوتر".[78][79][80] ابتداءً من عام 1927، عملت نوتر بشكل وثيق مع إميل آرتين وريتشارد براور وهلموت هاسه في الجبر غير التبادلي.[81][77]

كان وصول فان دير فاردن جزءاً من توافد رياضيين من مختلف أنحاء العالم إلى گوتنگن، التي غدت مركزاً رئيسياً للبحث الرياضي والفيزيائي. وكان الروسيان بافل ألكسندروف وبافل أوريسون أول هؤلاء عام 1923.[82] وبين 1926 و1930 حاضر ألكسندروف بانتظام في الجامعة، وأصبح صديقاً مقرباً لنوتر.[83] وكان يلقبها بـ der Noether مستخدماً der كصفة مميزة لا كأداة التعريف المذكرة الألمانية.[84] حاولت نوتر مساعدته للحصول على منصب أستاذ عادي في گوتنگن، لكنها لم تتمكن إلا من تأمين منحة له من مؤسسة روكفلر للدراسة في جامعة برنستون لعام 1927–1928.[85][86]

طلاب الدراسات العليا

في گوتنگن أشرفت نوتر على أكثر من عشرة طلاب دكتوراه؛[46] ومعظمهم بالاشتراك مع إدموند لاندو، إذ لم يُسمح لها بالإشراف على الأطروحات وحدها.[87][88] كانت أولهم غريته هيرمان التي ناقشت أطروحتها في فبراير 1925.[89] وهي معروفة بعملها في أسس ميكانيكا الكم، لكن أطروحتها كانت إسهاماً مهماً في نظرية المثالي.[90][91] وقد تحدثت لاحقاً عن نوتر بتبجيل ووصفتها بأنها "أم الأطروحة".[92]

في الفترة نفسها كتب كل من هاينريش غريل ورودولف هولزر أطروحتيهما بإشرافها. توفي هولزر بمرض السل قبل دفاعه.[93][94][95] أما غريل فقد دافع عن أطروحته عام 1926 وعمل لاحقاً في جامعة يينا وجامعة هاله قبل أن يفقد رخصته التدريسية عام 1935 بسبب اتهامات بأفعال مثلية.[46] وأعيد تأهيله لاحقاً ليصبح أستاذاً في جامعة هومبولت عام 1948.[46][96]

لاحقاً أشرفت نوتر على فيرنر فيبر[97] ويعقوب ليفيتسكي[98] اللذين دافعا عن أطروحتيهما عام 1929.[99][100] كان فيبر يُعتبر رياضياً متواضعاً،[101] وشارك لاحقاً في طرد الرياضيين اليهود من گوتنگن.[102] أما ليفيتسكي فعمل في جامعة ييل ثم الجامعة العبرية في القدس في الانتداب البريطاني على فلسطين، وأسهم إسهامات مهمة في نظرية الحلقات (منها مبرهنة ليفيتسكي ومبرهنة هوبكنز–ليفيتسكي).[103]

ومن بين "أولاد نوتر" أيضاً ماكس دورنغ، هانس فيتّينغ، إرنست فيت، تسن كيونغتزه، وأوتو شيلينغ. حصل دورنغ، الذي اعتُبر أبرز طلابها، على الدكتوراه عام 1930.[104][105] عمل في هامبورغ وماردن وگوتنگن،[106] وهو معروف بمساهماته في الهندسة الحسابية.[107] نال فيتّينغ الدكتوراه عام 1931 بأطروحة عن الزمر الأبيلية[108] ويُذكر بعمله في نظرية الزمر، خصوصاً مبرهنة فيتّينغ ولمّة فيتّينغ.[109] لكنه توفي في سن 31 بسبب مرض عظمي.[110]

أما فيت فقد بدأ تحت إشراف نوتر لكن بعد إقصائها عام 1933 أصبح تحت إشراف غوستاف هيرغلوستز.[111] نال الدكتوراه في يوليو 1933 بأطروحة عن مبرهنة ريمان–روخ ودوال زيتا.[112] وأحرز لاحقاً عدة نتائج تحمل اسمه.[113] أما تسن، المعروف بإثبات مبرهنة تسن، فنال الدكتوراه في ديسمبر 1933، وعاد إلى الصين عام 1935 ليُدرّس في جامعة تشيكيانغ الوطنية،[114] لكنه توفي بعد خمس سنوات فقط.[115]

بدأ شيلينغ كذلك دراسته تحت إشراف نوتر، لكنه اضطر لتغيير المشرف بعد هجرتها، فأكمل الدكتوراه تحت إشراف هلموت هاسه عام 1934 في جامعة ماربورغ.[116][117] عمل لاحقاً باحثاً في كلية ترينيتي (كامبريدج) قبل انتقاله إلى الولايات المتحدة.[46]

ومن طلاب نوتر الآخرين فيلهلم دورنته (نال الدكتوراه عام 1927 عن الزمر)،[118] فيرنر فوربك (عام 1935 عن حقول الانشطار),[46] وفولفغانغ فيشمان (عام 1936 عن النظرية p-adic).[119] لا تتوافر معلومات عن الأولين، أما فيشمان فقد دعم مبادرة طلابية حاولت دون نجاح إلغاء قرار فصل نوتر،[120] وتوفي لاحقاً جندياً على الجبهة الشرقية في الحرب العالمية الثانية.[46]

مدرسة نوتر

طوّرت نوتر دائرة مقرّبة من الرياضيين إلى جانب طلابها من الدراسات العليا، ممن شاركوها منهجها في الجبر التجريدي وساهموا في تطوّر هذا الحقل،[121] وعُرف هؤلاء غالبًا باسم "مدرسة نوتر".[122][123] من أمثلة ذلك تعاونها الوثيق مع فولفغانغ كرول، الذي قدّم إسهامات بارزة في الجبر التبادلي عبر مبرهنة المثالي الرئيسي (Hauptidealsatz) ونظرية الأبعاد في الحلقات التبادلية.[124] كما يُذكر غوتفريد كوثه، الذي طوّر نظرية الكميات فوق العقدية مستخدمًا مناهج نوتر وكرول.[124]

إلى جانب عبقريتها الرياضية، كانت نوتر موضع تقدير لاهتمامها بالآخرين. فقد كانت أحيانًا جافة في تعاملها مع من يخالفونها، لكنها اشتهرت بمساعدتها وصبرها في توجيه الطلاب الجدد. وقد جعلها إخلاصها للدقة الرياضية تُعرف بأنها "ناقدة صارمة"، لكنها جمعت بين هذا الحرص وبين روحٍ حاضنة.[125] وفي نعيه لها، وصفها فان در فاردن بأنها:

خالصة من الأنانية ومتحرّرة من الغرور، لم تنسب أي شيء إلى نفسها، بل رفعت من شأن أعمال طلابها قبل كل شيء.[126]

امتد تفاني نوتر لموضوعها ولطلابها إلى ما بعد الدوام الأكاديمي. ففي إحدى المرات، حين كان المبنى مغلقًا بسبب عطلة رسمية، جمعت الصف على السلالم الخارجية، ثم قادتهم عبر الغابة لتُحاضر عليهم في مقهى محلي.[127] ولاحقًا، بعد أن فصلتها ألمانيا النازية من التدريس، كانت تستضيف الطلاب في منزلها لمناقشة خططهم المستقبلية ومفاهيم رياضية.[128]

محاضرات مؤثرة

كان أسلوب حياة نوتر البسيط في البداية نتيجة حرمانها من راتب مقابل عملها. حتى بعد أن بدأتها الجامعة بدفع أجر زهيد عام 1923، ظلّت تعيش حياة متواضعة. وعندما أصبحت تُدفع لها رواتب أفضل لاحقًا، كانت تدّخر نصفها لتورثه لابن أخيها غوتفريد إي. نوتر.[129]

يرى كُتّاب سيرتها أنّها لم تكن معنية كثيرًا بالمظهر أو الآداب، مكرّسة جلّ اهتمامها لدراستها. فقد وصفت أولغا تاوسكي-تود، وهي عالمة جبر بارزة درست على يديها، مأدبة غداء حيث كانت نوتر "مستغرقة بالكامل في نقاش رياضي، تُشير بيديها بحماسة" أثناء الأكل، حتى إنها كانت تسكب الطعام على ثيابها وتمسحه غير آبهة.[130] كان الطلاب الحريصون على المظاهر ينزعجون وهي تستخرج المنديل من بلوزتها أو وهي تتجاهل اضطراب شعرها المتزايد أثناء المحاضرة. حتى إن طالبتين حاولتا التحدّث معها في استراحة محاضرة استمرت ساعتين، لكن لم تتمكنا من مقاطعة نقاشها الرياضي الحامي مع بقية الطلبة.[131]

لم تكن نوتر تلتزم بخطة دراسية في محاضراتها.[126] كانت تتكلم بسرعة، وغالبًا ما اعتُبرت محاضراتها صعبة الفهم حتى من قبل علماء كبار مثل كارل لودفيغ زيغل وبول دوبريل.[132][133] وكان الطلاب الذين لا يعجبهم أسلوبها يشعرون بالعزلة.[134] أما "الغرباء" الذين زاروا محاضراتها أحيانًا، فلم يكونوا يمكثون أكثر من نصف ساعة قبل مغادرة القاعة. قال أحد طلابها عن ذلك: "لقد هُزم العدو؛ انسحب تمامًا."[135]

كانت نوتر تتعامل مع محاضراتها كوقت نقاش حي مع طلابها، لتفكّر معهم وتوضّح مسائل رياضية مهمة. بعض من أهم نتائجها الرياضية خرجت من تلك المحاضرات، واعتمدت كتب رئيسية لاحقة مثل كتابَي فان در فاردن وماكس دويرينغ على مذكرات طلابها.[126] وقد نقلت حماسًا رياضيًا مُعديًا إلى طلابها الأكثر التزامًا، الذين كانوا يستمتعون بمحادثاتهم الحيّة معها.[136][137]

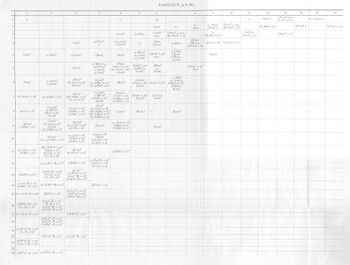

كان يحضر محاضراتها بعض زملائها أيضًا، وأحيانًا سمحت لغيرها (بمن فيهم طلابها) أن يُنشر عملها تحت أسمائهم، مما جعل جزءًا معتبرًا من إسهاماتها يظهر في أوراق بحثية لا تحمل اسمها.[138] وقد سُجّل أنها قدّمت خمس دورات فصلية على الأقل في گوتنگن:[139]

شتاء 1924–1925: نظرية الزُمَر والأعداد فوق العقدية

شتاء 1927–1928: الكميات فوق العقدية ونظرية التمثيلات

صيف 1928: جبر لاأبدي (غير تبادلي)

صيف 1929: حساب لاأبدي (غير تبادلي)

شتاء 1929–1930: جبر الكميات فوق العقدية

جامعة موسكو الحكومية

بين عامي 1928 و1929، قبلت نوتر دعوة من جامعة موسكو الحكومية، حيث واصلت العمل مع بافيل ألكسندروف. إلى جانب أبحاثها، قدّمت محاضرات في الجبر التجريدي والهندسة الجبرية. كما عملت مع الطوبولوجيين ليڤ پونترياگين ونيقولاي تشبوتاريوف، اللذين أشادا لاحقًا بإسهاماتها في تطوير نظرية گالوا.[140][141][142]

لم تكن السياسة محور حياتها، لكنها أولت اهتماماً كبيراً بها. فقد عبّر ألكسندروف عن أنّها أبدت دعمًا واضحًا للثورة الروسية، وكانت مبتهجة بإنجازات السوفيت في ميادين العلوم والرياضيات، معتبرة إيّاها فرصًا جديدة أتاحها المشروع البلشفي. هذا الموقف جلب لها مشاكل في ألمانيا، حتى إنها طُردت من سكنٍ للطالبات بعد أن اشتكى زملاؤها من "يهودية تميل إلى الماركسية".[143] وقد ذكر هيرمان فايل أنّه "خلال الفترة العاصفة بعد الثورة الألمانية 1918–1919،" كانت نوتر "تميل أكثر أو أقل نحو الحزب الديمقراطي الاجتماعي الألماني".[40] كما كانت عضوًا في الحزب الديمقراطي الاجتماعي المستقل بألمانيا بين 1919 و1922، وهو حزب قصير العمر انشق عن الحزب الأصلي. وبحسب المؤرخ كولن ماكلارتي: "لم تكن بلشفية، لكنها لم تخف من أن تُنعت بذلك".[144]

خططت نوتر للعودة إلى موسكو، وحظيت بدعم ألكسندروف في ذلك. وبعد مغادرتها ألمانيا عام 1933، حاول أن يساعدها للحصول على كرسي أستاذية في جامعة موسكو عبر وزارة التعليم السوفيتية، لكن المحاولة لم تنجح. مع ذلك، استمرت المراسلات بينهما خلال الثلاثينيات، وفي 1935 كانت تخطّط للعودة إلى الاتحاد السوفيتي.[143]

الاعتراف بفضلها

In 1932, Emmy Noether and Emil Artin received the Ackermann–Teubner Memorial Award for their contributions to mathematics.[77] The prize included a monetary reward of قالب:Reichsmark and was seen as a long-overdue official recognition of her considerable work in the field. Nevertheless, her colleagues expressed frustration at the fact that she was not elected to the Göttingen Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften (academy of sciences) and was never promoted to the position of Ordentlicher Professor[145][146] (full professor).[147]

Noether's colleagues celebrated her fiftieth birthday, in 1932, in typical mathematicians' style. Helmut Hasse dedicated an article to her in the Mathematische Annalen, wherein he confirmed her suspicion that some aspects of noncommutative algebra are simpler than those of commutative algebra, by proving a noncommutative reciprocity law.[148] This pleased her immensely. He also sent her a mathematical riddle, which he called the "mμν-riddle of syllables". She solved it immediately, but the riddle has been lost.[145][146]

In September of the same year, Noether delivered a plenary address (großer Vortrag) on "Hyper-complex systems in their relations to commutative algebra and to number theory" at the International Congress of Mathematicians in Zürich. The congress was attended by 800 people, including Noether's colleagues Hermann Weyl, Edmund Landau, and Wolfgang Krull. There were 420 official participants and twenty-one plenary addresses presented. Apparently, Noether's prominent speaking position was a recognition of the importance of her contributions to mathematics. The 1932 congress is sometimes described as the high point of her career.[146][149]

الطرد من گوتنگن من قِبل النازيين

When Adolf Hitler became the German Reichskanzler in January 1933, Nazi activity around the country increased dramatically. At the University of Göttingen, the German Student Association led the attack on the "un-German spirit" attributed to Jews and was aided by privatdozent and Noether's former student Werner Weber. Antisemitic attitudes created a climate hostile to Jewish professors. One young protester reportedly demanded: "Aryan students want Aryan mathematics and not Jewish mathematics."[150]

One of the first actions of Hitler's administration was the Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service which removed Jews and politically suspect government employees (including university professors) from their jobs unless they had "demonstrated their loyalty to Germany" by serving in World War I. In April 1933, Noether received a notice from the Prussian Ministry for Sciences, Art, and Public Education which read: "On the basis of paragraph 3 of the Civil Service Code of 7 April 1933, I hereby withdraw from you the right to teach at the University of Göttingen."[151][152] Several of Noether's colleagues, including Max Born and Richard Courant, also had their positions revoked.[151][152]

Noether accepted the decision calmly, providing support for others during this difficult time. Hermann Weyl later wrote that "Emmy Noether – her courage, her frankness, her unconcern about her own fate, her conciliatory spirit – was in the midst of all the hatred and meanness, despair and sorrow surrounding us, a moral solace."[150] Typically, Noether remained focused on mathematics, gathering students in her apartment to discuss class field theory. When one of her students appeared in the uniform of the Nazi paramilitary organization Sturmabteilung (SA), she showed no sign of agitation and, reportedly, even laughed about it later.[151][152]

اللجوء في برين مور وپرنستون

As dozens of newly unemployed professors began searching for positions outside of Germany, their colleagues in the United States sought to provide assistance and job opportunities for them. Albert Einstein and Hermann Weyl were appointed by the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, while others worked to find a sponsor required for legal immigration. Noether was contacted by representatives of two educational institutions: Bryn Mawr College, in the United States, and Somerville College at the University of Oxford, in England. After a series of negotiations with the Rockefeller Foundation, a grant to Bryn Mawr was approved for Noether and she took a position there, starting in late 1933.[153][154]

At Bryn Mawr, Noether met and befriended Anna Wheeler, who had studied at Göttingen just before Noether arrived there. Another source of support at the college was the Bryn Mawr president, Marion Edwards Park, who enthusiastically invited mathematicians in the area to "see Dr. Noether in action!"[155][156]

During her time at Bryn Mawr, Noether formed a group, sometimes called the Noether girls,[157] of four post-doctoral (Grace Shover Quinn, Marie Johanna Weiss, Olga Taussky-Todd, who all went on to have successful careers in mathematics) and doctoral students (Ruth Stauffer).[158] They enthusiastically worked through van der Waerden's Moderne Algebra I and parts of Erich Hecke's Theorie der algebraischen Zahlen (Theory of algebraic numbers).[159] Stauffer was Noether's only doctoral student in the United States, but Noether died shortly before she graduated.[160] She took her examination with Richard Brauer and received her degree in June 1935,[161] with a thesis concerning separable normal extensions.[162] After her doctorate, Stauffer worked as a teacher for a short period and as a statistician for over 30 years.[46][161]

In 1934, Noether began lecturing at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton upon the invitation of Abraham Flexner and Oswald Veblen.[163] She also worked with Abraham Albert and Harry Vandiver.[164] She remarked about Princeton University that she was not welcome at "the men's university, where nothing female is admitted".[165]

Her time in the United States was pleasant, as she was surrounded by supportive colleagues and absorbed in her favorite subjects.[166] In mid-1934, she briefly returned to Germany to see Emil Artin and her brother Fritz.[167] The latter, after having been forced out of his job at the Technische Hochschule Breslau, had accepted a position at the Research Institute for Mathematics and Mechanics in Tomsk, in the Siberian Federal District of Russia.[167]

Many of her former colleagues had been forced out of the universities, but she was able to use the library in Göttingen as a "foreign scholar". Without incident, Noether returned to the United States and her studies at Bryn Mawr.[168][169]

الوفاة

In April 1935, doctors discovered a tumor in Noether's pelvis. Worried about complications from surgery, they ordered two days of bed rest first. During the operation they discovered an ovarian cyst "the size of a large cantaloupe".[170] Two smaller tumors in her uterus appeared to be benign and were not removed to avoid prolonging surgery. For three days she appeared to convalesce normally, and she recovered quickly from a circulatory collapse on the fourth. On 14 April, Noether fell unconscious, her temperature soared to 109 °F (42.8 °C), and she died. "[I]t is not easy to say what had occurred in Dr. Noether", one of the physicians wrote. "It is possible that there was some form of unusual and virulent infection, which struck the base of the brain where the heat centers are supposed to be located." She was 53.[170]

A few days after Noether's death, her friends and associates at Bryn Mawr held a small memorial service at College President Park's house.[171] Hermann Weyl and Richard Brauer both traveled from Princeton and delivered eulogies.[172] In the months that followed, written tributes began to appear around the globe: Albert Einstein joined van der Waerden, Weyl, and Pavel Alexandrov in paying their respects.[5] Her body was cremated and the ashes interred under the walkway around the cloisters of the Old Library at Bryn Mawr.[173][174]

المساهمات في الرياضيات والفيزياء

كان لعمل إمي نوتر في الجبر المجرد والطوبولوجيا تأثير بالغ في الرياضيات، بينما كان لـ مبرهنة نوتر آثار واسعة في الفيزياء النظرية والنظم الديناميكية. أظهرت نوتر قدرة فائقة على التفكير التجريدي، مما مكنها من معالجة المسائل الرياضية بطرق جديدة وأصيلة.[42] وصف صديقها وزميلها هيرمان فايل إنتاجها العلمي في ثلاث مراحل:

(1) فترة الاعتماد النسبي: 1907–1919

(2) الأبحاث المتعلقة بالنظرية العامة للمثاليّات: 1920–1926

(3) دراسة الجبر غير التبديلية، وتمثيلاتها بالتحويلات الخطية، وتطبيقاتها على دراسة الحقول العددية التبديلية وحسابها

في المرحلة الأولى (1907–1919)، تناولت نوتر بشكل أساسي المتحولات التفاضلية والجبرية، بدءاً من أطروحتها تحت إشراف بول گوردان. ومع اتساع آفاقها الرياضية، أصبح عملها أكثر عمومية وتجريداً، خصوصاً بعد اطلاعها على أعمال دافيد هلبرت وتواصلها مع خلف گوردان، إرنست زيجسموند فيشر. وبعد انتقالها إلى گوتنگن عام 1915 بوقت قصير، أثبتت مبرهنتي نوتر، اللتين عُدّتا "من أهم المبرهنات الرياضية على الإطلاق في توجيه تطور الفيزياء الحديثة".[11]

في المرحلة الثانية (1920–1926)، كرّست نوتر جهودها لتطوير نظرية الحلقات الرياضية.[175] أما في المرحلة الثالثة (1927–1935)، فقد ركزت على الجبر غير التبديلية والتحويلات الخطية والحقول العددية التبديلية.[176] ورغم أن نتائج المرحلة الأولى كانت لافتة ومفيدة، إلا أن شهرتها بين الرياضيين تستند أكثر إلى أعمالها الرائدة في المرحلتين الثانية والثالثة، كما أشار هيرمان فايل وفان در فاردن في مراثيهما لها.[40][126]

في هذه المراحل، لم تكن نوتر تكتفي بتطبيق أفكار وأساليب الرياضيين السابقين، بل كانت تبتكر أنظمة جديدة من التعريفات الرياضية التي ستستخدمها الأجيال اللاحقة. فقد طورت، على وجه الخصوص، نظرية جديدة كلياً لـ المثاليّات في الحلقات، موسعةً أعمال ريتشارد ديديكند. وهي معروفة أيضاً بتطويرها "شرط السلسلة الصاعدة"، وهو شرط بسيط حول المحدودية أتاح لها الحصول على نتائج قوية.Rowe & Koreuber 2020, pp. 27–30 ساعدت مثل هذه الشروط ونظرية المثاليّات نوتر على تعميم نتائج قديمة ومعالجة مسائل تقليدية من منظور جديد، مثل موضوع المتحولات الجبرية التي كان والدها قد عمل عليها، ونظرية الحذف.

السياق التاريخي

في القرن الممتد من 1832 حتى وفاة نوتر عام 1935، شهد مجال الرياضيات — وخصوصاً الجبر — ثورة عميقة لا تزال آثارها ماثلة. كان رياضيو القرون السابقة يعملون على طرق عملية لحل أنواع معينة من المعادلات مثل الدوال التكعيبية والمعادلات من الدرجة الرابعة والمعادلات من الدرجة الخامسة، إضافة إلى مسألة جذور الوحدة وبناء المضلع المنتظم باستخدام الفرجار والمسطرة. بدءاً من برهان كارل فريدريش غاوس عام 1832 حول إمكانية تحليل الأعداد الأولية مثل 5 ضمن الأعداد الغاوسية،[177] مروراً بإدخال إيفاريست غالوا لمفهوم زمرة التبديلات عام 1832 (نُشرت أوراقه بعد وفاته عام 1846 على يد ليوڤيل)، وويليام روان هاملتون ووصفه لـ الكواتيرنيونات عام 1843، وآرثر كايلي الذي أعطى تعريفاً أكثر حداثة للزُمر عام 1854، أصبح البحث موجهاً لدراسة خصائص أنظمة أكثر تجريداً وعامة. وكانت مساهمات نوتر الأهم في تطوير هذا الميدان الجديد: الجبر المجرد.[178]

خلفية عن الجبر المجرد والرياضيات المفهومية

يُعد الزمر والحلقات من أبسط البنى في الجبر المجرد:

- الزمرة: مجموعة من العناصر وعملية واحدة تربط بين عنصرين لإنتاج عنصر ثالث. يجب أن تحقق هذه العملية شروطاً معينة: الإغلاق، والارتباطية، ووجود عنصر محايد، ووجود عنصر معكوس لكل عنصر.[179][180]

- الحلقة: تتكون أيضاً من مجموعة عناصر، لكن لها عمليتان. يجب أن تجعل العملية الأولى المجموعة زمرة تبديلية، أما الثانية فيجب أن تكون مرتبطة وموزعة بالنسبة إلى الأولى. قد تكون الحلقة تبديلية أو غير تبديلية.[181] وإذا امتلك كل عنصر غير صفري معكوساً ضربياً، سُمّيت حلقة قسمة، وإذا كانت تبديلية سميت حقلاً. الأعداد الصحيحة، مثلاً، تُكوّن حلقة تبديلية بعمليتي الجمع والضرب، لكنها ليست حلقة قسمة.[182][183]

أظهرت نوتر أن كثيراً من خصائص الأعداد الصحيحة يمكن تعميمها إلى الحلقات عبر صياغة نظريات جديدة، مثل مبرهنة لاسكر–نوتر الخاصة بالمثاليّات.[184] كما درست تمثيلات الزمر والوحدات المرتبطة بالحلقات، وأوضحت كيف تكشف هذه الأدوات عن بنى غير ظاهرة مباشرة. هذه المقاربة كانت جزءاً مما سمّته "الرياضيات المفهومية"، التي صارت سمة بارزة في أعمال الجبر الحديث.[185]

المرحلة الأولى (1908–1919)

نظرية الثبات الجبري

ارتبط جزء كبير من أعمال نوتر في الحقبة الأولى من مسيرتها بـ نظرية المتحولات، وبالأخص نظرية المتحولات الجبرية. تُعنى نظرية المتحولات بالتعابير التي تبقى ثابتة (غير متغيرة) تحت تأثير زمرة من التحويلات.[186] كمثال يومي، إذا ما دُوّر مسطرة مترية صلبة، فإن إحداثيات نهايتيها تتغير، لكن طولها يبقى كما هو. مثال أكثر تطوراً على "متحول" هو المميِّز B2 − 4AC لمتعددة حدود تربيعية متجانسة Ax2 + Bxy + Cy2، حيث x و y هما مجهولان. يُسمى هذا المميز "متحولاً" لأنه لا يتغير عند الإبدالات الخطية x → ax + by و y → cx + dy ذات المحدد ad − bc = 1. تُشكّل هذه الإبدالات الزمرة الخطية الخاصة SL2.[187] يمكن طرح السؤال عن جميع كثيرات الحدود في A و B و C التي لا تتغير بفعل SL2؛ حيث يتضح أن هذه هي كثيرات الحدود في المميِّز.[188] وبشكل أعم، يمكن السؤال عن متحولات متعدد حدود متجانس من الشكل A0xry0 + ... + Arx0yr من درجة أعلى، والتي ستكون بعض كثيرات الحدود في معاملات A0, ..., Ar. وبصورة أعم أيضاً، يمكن طرح سؤال مماثل لمتعددات الحدود المتجانسة في أكثر من متغيرين.[189]

كان أحد الأهداف الرئيسية لنظرية المتحولات هو حل "مشكلة الأساس المنتهي". فمجموع أو جداء أي متحولين هو متحول أيضاً، وتساءلت مشكلة الأساس المنتهي عما إذا كان من الممكن الحصول على جميع المتحولات ابتداءً من قائمة منتهية من المتحولات تُسمى مولدات، ثم بإجراء عمليات الجمع أو الضرب بينها.[190] على سبيل المثال، يشكل المميِّز أساساً منتهياً (بعنصر واحد) لمتحولات كثيرة الحدود التربيعية.[188]

كان مشرف نوتر، بول غوردان، يُعرف بـ "ملك نظرية المتحولات"، وكانت مساهمته الأساسية في الرياضيات هي حله سنة 1870 لمشكلة الأساس المنتهي لمتحولات كثيرات الحدود المتجانسة في متغيرين.[191][192] وقد أثبت ذلك من خلال تقديم طريقة بنائية لإيجاد جميع المتحولات ومولداتها، لكنه لم يتمكن من تطبيق هذه الطريقة البنائية على المتحولات في ثلاثة متغيرات أو أكثر. وفي سنة 1890، أثبت ديفيد هيلبرت بياناً مشابهاً لمتحولات كثيرات الحدود المتجانسة في أي عدد من المتغيرات.[193][194] علاوةً على ذلك، فقد نجحت طريقته ليس فقط مع الزمرة الخطية الخاصة، بل أيضاً مع بعض زُمرها الجزئية مثل الزمرة المتعامدة الخاصة.[195]

سارت نوتر على نهج غوردان، فكتبت أطروحتها للدكتوراه وعدداً من المنشورات الأخرى في نظرية المتحولات. وقد وسعت نتائج غوردان وبنت أيضاً على أبحاث هيلبرت. ولاحقاً، كانت تنتقد هذا العمل، معتبرة إياه قليل الأهمية ومعترفة بأنها نسيت تفاصيله.[196] وكتب هيرمان فايل:

إنه من الصعب تخيل تناقض أكبر من بين ورقتها الأولى، الأطروحة، وأعمال نضجها؛ فالأولى مثال صارخ على الحسابات الشكلية، بينما الأخيرة تمثل مثالاً بالغ العظمة على التفكير المفهومي البديهي في الرياضيات.[197]

نظرية غالوا

تهتم نظرية غالوا بالتحويلات في الحقول العددية التي تقوم بـ تبديل جذور معادلة ما.[198] لنفترض معادلة كثير حدود في متغير x من الدرجة n، حيث تُستمد المعاملات من حقل أساس ما، قد يكون مثلاً حقل الأعداد الحقيقية، أو الأعداد النسبية، أو عدد صحيح بتطبيق المعيار 7. قد توجد أو لا توجد قيم لـ x تجعل هذا كثير الحدود يساوي صفراً. وتسمى هذه القيم، إن وُجدت، الجذور.[199] على سبيل المثال، إذا كان كثير الحدود هو x2 + 1 وكان الحقل هو الأعداد الحقيقية، فإن كثير الحدود لا يملك جذوراً، لأن أي اختيار لـ x يجعله أكبر من أو يساوي واحداً.[200] وإذا تم توسيع الحقل فقد يكتسب كثير الحدود جذوراً،[201] وإذا توسع بما فيه الكفاية، فإنه دائماً يملك عدداً من الجذور مساوياً لدرجته.[202]

بمتابعة المثال السابق، إذا تم توسيع الحقل إلى الأعداد العقدية، فإن كثير الحدود يكتسب جذرين هما +i و−i، حيث إن i هو الوحدة التخيلية، أي i 2 = −1. وبصورة أعم، فإن الحقل الممتد الذي يمكن فيه تحليل كثير الحدود إلى جذوره يُعرف باسم حقل الانشطار.[203]

زمرة غالوا لكثير حدود ما هي مجموعة جميع التحويلات لحقل الانشطار التي تحفظ الحقل الأساس وجذور كثير الحدود.[204] (وتسمى هذه التحويلات تشاكلات). تتكون زمرة غالوا لـ x2 + 1 من عنصرين: التحويل المحايد، الذي يرسل كل عدد عقدي إلى نفسه، والمرافق العقدي، الذي يرسل +i إلى −i. وبما أن زمرة غالوا لا تغيّر الحقل الأساس، فهي تترك معاملات كثير الحدود دون تغيير، وبالتالي يجب أن تترك مجموعة الجذور ثابتة. كل جذر يمكن أن ينتقل إلى جذر آخر، لذا فإن كل تحويل يحدد تبديلة لجذور n فيما بينها. وتكمن أهمية زمرة غالوا في المبرهنة الأساسية في نظرية غالوا، التي تثبت أن الحقول الواقعة بين الحقل الأساس وحقل الانشطار تقابل واحداً لواحد مع الزُمر الجزئية لزمرة غالوا.[205]

في عام 1918، نشرت نوتر مقالة حول المسألة العكسية لغالوا.[206] فبدلاً من تحديد زمرة غالوا للتحويلات لحقل معطى وامتداداته، تساءلت نوتر عما إذا كان، بالنظر إلى حقل وزمرة، من الممكن دائماً إيجاد امتداد للحقل تكون له هذه الزمرة كزمرة غالوا. وقامت بتبسيط ذلك إلى "مشكلة نوتر"، التي تسأل عما إذا كان الحقل الثابت لزُمرة جزئية G من الزمرة المتناظرة Sn التي تؤثر في الحقل k(x1, ..., xn) دائماً امتداداً متسامياً خالصاً للحقل k. (وقد ذكرت هذه المسألة أول مرة في ورقة عام 1913،[207] حيث نسبت الفكرة إلى زميلها فيشر.) وقد أظهرت أن هذا صحيح عندما n = 2 أو 3 أو 4. وفي عام 1969، وجد ريتشارد سوان مثالاً مضاداً لمشكلة نوتر عندما n = 47 وG زمرة دورية من الرتبة 47[208] (مع أن هذه الزمرة يمكن تحقيقها كـ زمرة غالوا على الأعداد النسبية بطرق أخرى). وما تزال المسألة العكسية لغالوا غير محلولة حتى اليوم.[209]

Physics

Noether was brought to Göttingen in 1915 by David Hilbert and Felix Klein, who wanted her expertise in invariant theory to help them in understanding general relativity,[210] a geometrical theory of gravitation developed mainly by Albert Einstein. Hilbert had observed that the conservation of energy seemed to be violated in general relativity, because gravitational energy could itself gravitate. Noether provided the resolution of this paradox, and a fundamental tool of modern theoretical physics, in a 1918 paper.[211] This paper presented two theorems, of which the first is known as Noether's theorem.[212] Together, these theorems not only solve the problem for general relativity, but also determine the conserved quantities for every system of physical laws that possesses some continuous symmetry.[213] Upon receiving her work, Einstein wrote to Hilbert:

Yesterday I received from Miss Noether a very interesting paper on invariants. I'm impressed that such things can be understood in such a general way. The old guard at Göttingen should take some lessons from Miss Noether! She seems to know her stuff.[214]

For illustration, if a physical system behaves the same, regardless of how it is oriented in space, the physical laws that govern it are rotationally symmetric; from this symmetry, Noether's theorem shows the angular momentum of the system must be conserved.[215][216] The physical system itself need not be symmetric; a jagged asteroid tumbling in space conserves angular momentum despite its asymmetry. Rather, the symmetry of the physical laws governing the system is responsible for the conservation law. As another example, if a physical experiment works the same way at any place and at any time, then its laws are symmetric under continuous translations in space and time; by Noether's theorem, these symmetries account for the conservation laws of linear momentum and energy within this system, respectively.[217][218]

At the time, physicists were not familiar with Sophus Lie's theory of continuous groups, on which Noether had built. Many physicists first learned of Noether's theorem from an article by Edward Lee Hill that presented only a special case of it. Consequently, the full scope of her result was not immediately appreciated.[219] During the latter half of the 20th century, Noether's theorem became a fundamental tool of modern theoretical physics, because of the insight it gives into conservation laws, and also as a practical calculation tool. Her theorem allows researchers to determine the conserved quantities from the observed symmetries of a physical system. Conversely, it facilitates the description of a physical system based on classes of hypothetical physical laws. For illustration, suppose that a new physical phenomenon is discovered. Noether's theorem provides a test for theoretical models of the phenomenon: If the theory has a continuous symmetry, then Noether's theorem guarantees that the theory has a conserved quantity, and for the theory to be correct, this conservation must be observable in experiments.[8]

Second epoch (1920–1926)

Ascending and descending chain conditions

In this epoch, Noether became famous for her deft use of ascending (Teilerkettensatz) or descending (Vielfachenkettensatz) chain conditions.[220] A sequence of non-empty subsets A1, A2, A3, ... of a set S is usually said to be ascending if each is a subset of the next:

Conversely, a sequence of subsets of S is called descending if each contains the next subset:

A chain becomes constant after a finite number of steps if there is an n such that for all m ≥ n. A collection of subsets of a given set satisfies the ascending chain condition if every ascending sequence becomes constant after a finite number of steps. It satisfies the descending chain condition if any descending sequence becomes constant after a finite number of steps.[221] Chain conditions can be used to show that every set of sub-objects has a maximal/minimal element, or that a complex object can be generated by a smaller number of elements.[222]

Many types of objects in abstract algebra can satisfy chain conditions, and usually if they satisfy an ascending chain condition, they are called Noetherian in her honor.[223] By definition, a Noetherian ring satisfies an ascending chain condition on its left and right ideals, whereas a Noetherian group is defined as a group in which every strictly ascending chain of subgroups is finite. A Noetherian module is a module in which every strictly ascending chain of submodules becomes constant after a finite number of steps.[224][225] A Noetherian space is a topological space whose open subsets satisfy the ascending chain condition;[ت] this definition makes the spectrum of a Noetherian ring a Noetherian topological space.[226][227]

The chain condition often is "inherited" by sub-objects. For example, all subspaces of a Noetherian space are Noetherian themselves; all subgroups and quotient groups of a Noetherian group are Noetherian; and, mutatis mutandis, the same holds for submodules and quotient modules of a Noetherian module.[228] The chain condition also may be inherited by combinations or extensions of a Noetherian object. For example, finite direct sums of Noetherian rings are Noetherian, as is the ring of formal power series over a Noetherian ring.[229]

Another application of such chain conditions is in Noetherian induction – also known as well-founded induction – which is a generalization of mathematical induction. It frequently is used to reduce general statements about collections of objects to statements about specific objects in that collection. Suppose that S is a partially ordered set. One way of proving a statement about the objects of S is to assume the existence of a counterexample and deduce a contradiction, thereby proving the contrapositive of the original statement. The basic premise of Noetherian induction is that every non-empty subset of S contains a minimal element. In particular, the set of all counterexamples contains a minimal element, the minimal counterexample. In order to prove the original statement, therefore, it suffices to prove something seemingly much weaker: For any counter-example, there is a smaller counter-example.[230]

Commutative rings, ideals, and modules

Noether's paper, Idealtheorie in Ringbereichen (Theory of Ideals in Ring Domains, 1921),[231] is the foundation of general commutative ring theory, and gives one of the first general definitions of a commutative ring.[ث][232] Before her paper, most results in commutative algebra were restricted to special examples of commutative rings, such as polynomial rings over fields or rings of algebraic integers. Noether proved that in a ring which satisfies the ascending chain condition on ideals, every ideal is finitely generated. In 1943, French mathematician Claude Chevalley coined the term Noetherian ring to describe this property.[232] A major result in Noether's 1921 paper is the Lasker–Noether theorem, which extends Lasker's theorem on the primary decomposition of ideals of polynomial rings to all Noetherian rings.[45][233] The Lasker–Noether theorem can be viewed as a generalization of the fundamental theorem of arithmetic which states that any positive integer can be expressed as a product of prime numbers, and that this decomposition is unique.[184]

Noether's work Abstrakter Aufbau der Idealtheorie in algebraischen Zahl- und Funktionenkörpern (Abstract Structure of the Theory of Ideals in Algebraic Number and Function Fields, 1927)[234] characterized the rings in which the ideals have unique factorization into prime ideals (now called Dedekind domains).[235] Noether showed that these rings were characterized by five conditions: they must satisfy the ascending and descending chain conditions, they must possess a unit element, but no zero divisors, and they must be integrally closed in their associated field of fractions.[235][236] This paper also contains what now are called the isomorphism theorems,[237] which describe some fundamental natural isomorphisms, and some other basic results on Noetherian and Artinian modules.[238]

Elimination theory

In 1923–1924, Noether applied her ideal theory to elimination theory in a formulation that she attributed to her student, Kurt Hentzelt. She showed that fundamental theorems about the factorization of polynomials could be carried over directly.[239][240][241]

Traditionally, elimination theory is concerned with eliminating one or more variables from a system of polynomial equations, often by the method of resultants.[242] For illustration, a system of equations often can be written in the form

- Mv = 0

where a matrix (or linear transform) M (without the variable x) times a vector v (that only has non-zero powers of x) is equal to the zero vector, 0. Hence, the determinant of the matrix M must be zero, providing a new equation in which the variable x has been eliminated.

Invariant theory of finite groups

Techniques such as Hilbert's original non-constructive solution to the finite basis problem could not be used to get quantitative information about the invariants of a group action, and furthermore, they did not apply to all group actions. In her 1915 paper,[243] Noether found a solution to the finite basis problem for a finite group of transformations G acting on a finite-dimensional vector space over a field of characteristic zero. Her solution shows that the ring of invariants is generated by homogeneous invariants whose degree is less than, or equal to, the order of the finite group; this is called Noether's bound. Her paper gave two proofs of Noether's bound, both of which also work when the characteristic of the field is coprime to (the factorial of the order of the group G). The degrees of generators need not satisfy Noether's bound when the characteristic of the field divides the number ,[244] but Noether was not able to determine whether this bound was correct when the characteristic of the field divides but not . For many years, determining the truth or falsehood of this bound for this particular case was an open problem, called "Noether's gap". It was finally solved independently by Fleischmann in 2000 and Fogarty in 2001, who both showed that the bound remains true.[245][246]

In her 1926 paper,[247] Noether extended Hilbert's theorem to representations of a finite group over any field; the new case that did not follow from Hilbert's work is when the characteristic of the field divides the order of the group. Noether's result was later extended by William Haboush to all reductive groups by his proof of the Mumford conjecture.[248] In this paper Noether also introduced the Noether normalization lemma, showing that a finitely generated domain A over a field k has a set {x1, ..., xn} of algebraically independent elements such that A is integral over k[x1, ..., xn].

الطبولوجيا

As noted by Hermann Weyl in his obituary, Noether's contributions to topology illustrate her generosity with ideas and how her insights could transform entire fields of mathematics.[40] In topology, mathematicians study the properties of objects that remain invariant even under deformation, properties such as their connectedness. An old joke is that "a topologist cannot distinguish a donut from a coffee mug", since they can be continuously deformed into one another.[249]

Noether is credited with fundamental ideas that led to the development of algebraic topology from the earlier combinatorial topology, specifically, the idea of homology groups.[250] According to Alexandrov, Noether attended lectures given by him and Heinz Hopf in 1926 and 1927, where "she continually made observations which were often deep and subtle"[251] and he continues that,

When ... she first became acquainted with a systematic construction of combinatorial topology, she immediately observed that it would be worthwhile to study directly the groups of algebraic complexes and cycles of a given polyhedron and the subgroup of the cycle group consisting of cycles homologous to zero; instead of the usual definition of Betti numbers, she suggested immediately defining the Betti group as the complementary (quotient) group of the group of all cycles by the subgroup of cycles homologous to zero. This observation now seems self-evident, but in those years (1925–1928) this was a completely new point of view.[252]

Noether's suggestion that topology be studied algebraically was adopted immediately by Hopf, Alexandrov, and others,[252] and it became a frequent topic of discussion among the mathematicians of Göttingen.[253] Noether observed that her idea of a Betti group makes the Euler–Poincaré formula simpler to understand, and Hopf's own work on this subject[254] "bears the imprint of these remarks of Emmy Noether".[255] Noether mentions her own topology ideas only as an aside in a 1926 publication,[256] where she cites it as an application of group theory.[257]

This algebraic approach to topology was also developed independently in Austria. In a 1926–1927 course given in Vienna, Leopold Vietoris defined a homology group, which was developed by Walther Mayer into an axiomatic definition in 1928.[258]

Third epoch (1927–1935)

Hypercomplex numbers and representation theory

Much work on hypercomplex numbers and group representations was carried out in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, but remained disparate. Noether united these earlier results and gave the first general representation theory of groups and algebras.[259][260] This single work by Noether was said to have ushered in a new period in modern algebra and to have been of fundamental importance for its development.[261]

Briefly, Noether subsumed the structure theory of associative algebras and the representation theory of groups into a single arithmetic theory of modules and ideals in rings satisfying ascending chain conditions.[260]

Noncommutative algebra

Noether also was responsible for a number of other advances in the field of algebra. With Emil Artin, Richard Brauer, and Helmut Hasse, she founded the theory of central simple algebras.[262]

A paper by Noether, Hasse, and Brauer pertains to division algebras,[263] which are algebraic systems in which division is possible. They proved two important theorems: a local-global theorem stating that if a finite-dimensional central division algebra over a number field splits locally everywhere then it splits globally (so is trivial), and from this, deduced their Hauptsatz ("main theorem"):

Every finite-dimensional central division algebra over an algebraic number field F splits over a cyclic cyclotomic extension.

These theorems allow one to classify all finite-dimensional central division algebras over a given number field. A subsequent paper by Noether showed, as a special case of a more general theorem, that all maximal subfields of a division algebra D are splitting fields.[264] This paper also contains the Skolem–Noether theorem, which states that any two embeddings of an extension of a field k into a finite-dimensional central simple algebra over k are conjugate. The Brauer–Noether theorem[265] gives a characterization of the splitting fields of a central division algebra over a field.[266]

الذكرى

Noether's work continues to be relevant for the development of theoretical physics and mathematics, and she is considered one of the most important mathematicians of the twentieth century.[174][268] During her lifetime and even until today, Noether has also been characterized as the greatest woman mathematician in recorded history[6][7][269] by mathematicians such as Pavel Alexandrov,[270] Hermann Weyl,[271] and Jean Dieudonné.[272]

In a letter to The New York Times, Albert Einstein wrote:[5]

In the judgment of the most competent living mathematicians, Fräulein Noether was the most significant creative mathematical genius thus far produced since the higher education of women began. In the realm of algebra, in which the most gifted mathematicians have been busy for centuries, she discovered methods which have proved of enormous importance in the development of the present-day younger generation of mathematicians.

In his obituary, fellow algebraist B. L. van der Waerden says that her mathematical originality was "absolute beyond comparison",[273] and Hermann Weyl said that Noether "changed the face of [abstract] algebra by her work".[12] Mathematician and historian Jeremy Gray wrote that any textbook on abstract algebra bears the evidence of Noether's contributions: "Mathematicians simply do ring theory her way."[223] Several things now bear her name, including many mathematical objects,[223] and an asteroid, 7001 Noether.[274]

انظر أيضاً

Notes

- ^ ألمانية: [ˈnøːtɐ]

- ^ أ ب إمي هو Rufname، أي الاسم الثاني من الاسمين الرسميين، والمخصص للاستخدام اليومي. يظهر ذلك في السيرة الذاتية التي قدمتها نوتر إلى جامعة إرلانگن–نورمبرگ عام 1907.[1][2] أحياناً يُظن خطأً أن إمي هو اختصار لـ أمالي، أو يُسجل خطأً باسم إميلي؛ على سبيل المثال استخدم لي سمولين الاسم الأخير في رسالة لـ The Reality Club.[3]

- ^ Or whose closed subsets satisfy the descending chain condition.[226]

- ^ The first definition of an abstract ring was given by Abraham Fraenkel in 1914, but the definition in current use was initially formulated by Masazo Sono in a 1917 paper.[232]

References

- ^ Noether 1983, p. iii.

- ^ Tollmien, Cordula, "Emmy Noether (1882–1935) – Lebensläufe", physikerinnen.de, archived from the original on 29 September 2007, retrieved 13 April 2024

- ^ Smolin, Lee (21 March 1999), "Lee Smolin on 'Special Relativity: Why Cant You Go Faster Than Light?' by W. Daniel Hillis; Hillis Responds", Edge.org, مؤسسة إدج, archived from the original on 30 July 2012, retrieved 6 March 2012,

But I think very few non-experts will have heard either of it or its maker – Emily Noether, a great German mathematician. ... This also requires Emily Noether's insight, that conserved quantities have to do with symmetries of natural law.

- ^ Conover, Emily (12 June 2018), "In her short life, mathematician Emmy Noether changed the face of physics", Science News, archived from the original on 26 March 2023, retrieved 2 July 2018

- ^ أ ب ت Einstein, Albert (1 May 1935), "The Late Emmy Noether: Professor Einstein Writes in Appreciation of a Fellow-Mathematician", نيويورك تايمز (published 4 May 1935), retrieved 13 April 2008 Transcribed online at the أرشيف تاريخ الرياضيات ماكتيوتر.

- ^ أ ب Alexandrov 1981, p. 100.

- ^ أ ب Kimberling 1982.

- ^ أ ب Ne'eman, Yuval, The Impact of Emmy Noether's Theorems on XXIst Century Physics in Teicher 1999, pp. 83–101.

- ^ أ ب ت Ogilvie & Harvey 2000, p. 949.

- ^ Weyl 1935

- ^ أ ب Lederman & Hill 2004, p. 73.

- ^ أ ب Dick 1981, p. 128

- ^ Dick 1981, p. 4.

- ^ Dick 1981, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Dick 1981, pp. 9–10.

- ^ Dick 1981, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Dick 1981, p. 15.

- ^ Dick 1981, pp. 15, 19–20.

- ^ O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Fritz Alexander Ernst Noether", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews..

- ^ Dick 1981, pp. 25, 45.

- ^ Kimberling 1981, p. 5.

- ^ أ ب Dick 1981, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Dick 1981, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Kimberling 1981, p. 10.

- ^ Kimberling 1981, pp. 8–10.

- ^ Lederman & Hill 2004, p. 71.

- ^ Dick 1981, p. 14.

- ^ Rowe 2021, p. 18.

- ^ Dick 1981, pp. 14–15.

- ^ أ ب Noether 1908.

- ^ Dick 1981, pp. 16–18.

- ^ Merzbach 1983, p. 164.

- ^ أ ب Kimberling 1981, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Dick 1981, pp. 13–17.

- ^ Dick 1981, pp. 18, 24.

- ^ Dick 1981, p. 18.

- ^ Kosmann-Schwarzbach 2011, p. 44.

- ^ Dick 1981, p. 23.

- ^ Rowe 2021, p. 22.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Weyl 1935.

- ^ Dick 1981, pp. 23–24.

- ^ أ ب Kimberling 1981, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Dick 1981, pp. 18–24.

- ^ Rowe 2021, pp. 29–35.

- ^ أ ب Rowe & Koreuber 2020, p. 27.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F. (November 2014), "Emmy Noether's doctoral students", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews.

- ^ Falckenberg 1912.

- ^ Seidelmann 1917.

- ^ Dick 1981, p. 16.

- ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^ أ ب ت خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةMactutor Biography - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^ Rowe & Koreuber 2020, p. 32.

- ^ Dick 1981, pp. 56–57.

- ^ Rowe 2021, p. x.

- ^ أ ب Dick 1981, p. 57.

- ^ Dick 1981, pp. 37–49.

- ^ أ ب ت ث van der Waerden 1935.

- ^ Mac Lane 1981, p. 71.

- ^ Dick 1981, p. 76.

- ^ Dick 1981, pp. 46–48.

- ^ Taussky 1981, p. 80.

- ^ Dick 1981, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Rowe & Koreuber 2020, p. 21, 122.

- ^ Dick 1981, pp. 37–38.

- ^ Mac Lane 1981, p. 77.

- ^ Dick 1981, p. 41.

- ^ Rowe & Koreuber 2020, pp. 36, 99.

- ^ Dick 1981, p. 38.

- ^ Lederman & Hill 2004, p. 74.

- ^ Scharlau, Winfried, Emmy Noether's Contributions to the Theory of Algebras in Teicher 1999, p. 49.

- ^ Dick 1981, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Kimberling 1981, p. 26.

- ^ Alexandrov 1981, pp. 108–110.

- ^ أ ب Alexandrov 1981, pp. 106–109.

- ^ McLarty 2005.

- ^ أ ب Dick 1981, pp. 72–73.

- ^ أ ب ت Kimberling 1981, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Dick 1981, p. 188.

- ^ Hasse 1933, p. 731.

- ^ Dick 1981, pp. 74–75.

- ^ أ ب Kimberling 1981, p. 29.

- ^ أ ب ت Dick 1981, pp. 75–76.

- ^ أ ب ت Kimberling 1981, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Dick 1981, pp. 78–79.

- ^ Kimberling 1981, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Kimberling 1981, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Dick 1981, p. 80.

- ^ Rowe 2021, p. 222.

- ^ Rowe 2021, pp. 223.

- ^ Dick 1981, pp. 80–81.

- ^ Dick 1981, pp. 85–86.

- ^ أ ب Rowe 2021, p. 251.

- ^ Stauffer 1936.

- ^ "Emmy Noether at the Institute for Advanced Study", StoryMaps, ArcGIS, 7 December 2019, archived from the original on 16 April 2024, retrieved 28 August 2020

- ^ Dick 1981, pp. 81–82.

- ^ Dick 1981, p. 81.

- ^ Dick 1981, p. 83.

- ^ أ ب Dick 1981, pp. 82–83.

- ^ Dick 1981, p. 82.

- ^ Kimberling 1981, p. 34.

- ^ أ ب Kimberling 1981, pp. 37–38.

- ^ Rowe 2021, p. 252.

- ^ Rowe 2021, pp. 252, 257.

- ^ Kimberling 1981, p. 39.

- ^ أ ب Chodos, Alan, ed. (March 2013), "This Month in Physics History: March 23, 1882: Birth of Emmy Noether", APSNews (in الإنجليزية), American Physical Society, 22 (3), archived from the original on 14 July 2024, retrieved 28 August 2020

- ^ Gilmer 1981, p. 131.

- ^ Kimberling 1981, pp. 10–23.

- ^ Gauss, Carl F. (1832), "Theoria residuorum biquadraticorum – Commentatio secunda", Comm. Soc. Reg. Sci. Göttingen (in اللاتينية), 7: 1–34 Reprinted in Werke [Complete Works of C.F. Gauss], Hildesheim: Georg Olms Verlag, 1973, pp. 93–148

- ^ Noether 1987, p. 168.

- ^ Lang 2005, II.§1.

- ^ Stewart 2015, pp. 18–19.

- ^ Stewart 2015, p. 182.

- ^ Stewart 2015, p. 183.

- ^ Gowers et al. 2008, p. 284.

- ^ أ ب Osofsky 1994.

- ^ Gowers et al. 2008, p. 801.

- ^ Dieudonné & Carrell 1970.

- ^ Lehrer, Gus (January 2015), "The fundamental theorems of invariant theory classical, quantum and super" (PDF) (Lecture notes), جامعة سيدني, p. 8, archived (PDF) from the original on 9 February 2025, retrieved 9 February 2025

- ^ أ ب Schur 1968, p. 45.

- ^ Schur 1968.

- ^ Reid 1996, p. 30.

- ^ Noether 1914, p. 11.

- ^ Gordan 1870.

- ^ Weyl 1944, pp. 618–621.

- ^ Hilbert 1890, p. 531.

- ^ Hilbert 1890, p. 532.

- ^ Dick 1981, pp. 16–18,155–156.

- ^ Dick 1981, p. 120.

- ^ Stewart 2015, pp. 108–111

- ^ Stewart 2015, pp. 22-23.

- ^ Stewart 2015, pp. 23, 39.

- ^ Stewart 2015, pp. 39, 129.

- ^ Stewart 2015, pp. 44, 129, 148.

- ^ Stewart 2015, pp. 129–130

- ^ Stewart 2015, pp. 112–114

- ^ Stewart 2015, pp. 114–116, 151–153

- ^ Noether 1918.

- ^ Noether 1913.

- ^ Swan 1969, p. 148.

- ^ Malle & Matzat 1999.

- ^ Gowers et al. 2008, p. 800.

- ^ Noether 1918b

- ^ Kosmann-Schwarzbach 2011, p. 25

- ^ Lynch, Peter (18 June 2015), "Emmy Noether's beautiful theorem", ThatsMaths, archived from the original on 9 December 2023, retrieved 28 August 2020

- ^ Kimberling 1981, p. 13

- ^ Zee 2016, p. 180.

- ^ Lederman & Hill 2004, pp. 97–116.

- ^ Taylor 2005, pp. 268–272.

- ^ Baez, John C. (2022), "Getting to the Bottom of Noether's Theorem", in Read, James; Teh, Nicholas J. (eds.), The Philosophy and Physics of Noether's Theorems, Cambridge University Press, pp. 66–99, arXiv:2006.14741, ISBN 9781108786812

- ^ Kosmann-Schwarzbach 2011, pp. 26, 101–102

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةACC - ^ Atiyah & MacDonald 1994, p. 74.

- ^ Atiyah & MacDonald 1994, pp. 74–75.

- ^ أ ب ت Gray 2018, p. 294.

- ^ Goodearl & Warfield Jr. 2004, pp. 1–3.

- ^ Lang 2002, pp. 413–415.

- ^ أ ب Hartshorne 1977, p. 5.

- ^ Atiyah & MacDonald 1994, p. 79.

- ^ Lang 2002, p. 414.

- ^ Lang 2002, p. 415–416.

- ^ Klappenecker, Andreas (Fall 2008), "Noetherian induction" (PDF), CPSC 289 Special Topics on Discrete Structures for Computing (Lecture notes), Texas A&M University, archived (PDF) from the original on 4 July 2024, retrieved 14 January 2025

- ^ Noether 1921.

- ^ أ ب ت Gilmer 1981, p. 133.

- ^ Rowe 2021, p. xvi.

- ^ Noether 1927.

- ^ أ ب Noether 1983, p. 13.

- ^ Rowe 2021, p. 96.

- ^ Rowe 2021, pp. 286–287.

- ^ Noether 1983, p. 14.

- ^ Noether 1923.

- ^ Noether 1923b.

- ^ Noether 1924.

- ^ Cox, Little & O'Shea 2015, p. 121.

- ^ Noether 1915.

- ^ Fleischmann 2000, p. 24.

- ^ Fleischmann 2000, p. 25.

- ^ Fogarty 2001, p. 5.

- ^ Noether 1926.

- ^ Haboush 1975.

- ^ Hubbard & West 1991, p. 204.

- ^ Hilton 1988, p. 284.

- ^ Dick 1981, p. 173.

- ^ أ ب Dick 1981, p. 174.

- ^ Hirzebruch, Friedrich, Emmy Noether and Topology in Teicher 1999, pp. 57–61

- ^ Hopf 1928.

- ^ Dick 1981, pp. 174–175.

- ^ Noether 1926b.

- ^ Hirzebruch, Friedrich, Emmy Noether and Topology in Teicher 1999, p. 63

- ^ Hirzebruch, Friedrich, Emmy Noether and Topology in Teicher 1999, pp. 61–63

- ^ Noether 1929.

- ^ أ ب Rowe 2021, p. 127.

- ^ van der Waerden 1985, p. 244.

- ^ Lam 1981, pp. 152–153.

- ^ Brauer, Hasse & Noether 1932.

- ^ Noether 1933.

- ^ Brauer & Noether 1927.

- ^ Roquette 2005, p. 6.

- ^ "Emmy-Noether Campus (ENC)", University of Siegen, archived from the original on 7 December 2024, retrieved 6 December 2024

- ^ Plumer, Brad (23 March 2016), "Emmy Noether revolutionized mathematics — and still faced sexism all her life", Vox, archived from the original on 7 September 2024, retrieved 2 November 2024

- ^ James 2002, p. 321.

- ^ Dick 1981, p. 154.

- ^ Dick 1981, p. 152.

- ^ Noether 1987, p. 167.

- ^ Dick 1981, p. 100.

- ^ Schmadel 2003, p. 270.

Sources

- Alexandrov, Pavel S. (1981), "In Memory of Emmy Noether", in Brewer, James W; Smith, Martha K. (eds.), Emmy Noether: A Tribute to Her Life and Work, New York: Marcel Dekker, pp. 99–111, ISBN 978-0-8247-1550-2, OCLC 7837628

- Atiyah, Michael; MacDonald, Ian G. (1994), Introduction to Commutative Algebra, Addison-Wesley and Avalon Publishing, ISBN 978-0201407518

- Byers, Nina (December 1996). "E. Noether's Discovery of the Deep Connection Between Symmetries and Conservation Laws" in Proceedings of a Symposium on the Heritage of Emmy Noether., Bar-Ilan University.

- Byers, Nina (2006), "Emmy Noether", in Byers, Nina; Williams, Gary (eds.), Out of the Shadows: Contributions of 20th Century Women to Physics, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-82197-1

- Cox, David A.; Little, John B.; O'Shea, Donal (2015), Ideals, Varieties, and Algorithms: An Introduction to Computational Algebraic Geometry and Commutative Algebra, Undergraduate Texts in Mathematics (4th ed.), Springer, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-16721-3, ISBN 978-3-319-16721-3

- Deuring, Max (1932), "Zur arithmetischen Theorie der algebraischen Funktionen" [On the Arithmetic Theory of Algebraic Functions], Mathematische Annalen (in الألمانية), 106 (1): 77–102, doi:10.1007/BF01455878

- Dick, Auguste (1981), Emmy Noether: 1882–1935, translated by Blocher, H.I., Boston: Birkhäuser, doi:10.1007/978-1-4684-0535-4, ISBN 978-3-7643-3019-4

- Ding, Shisun; Kang, Ming-Chang; Tan, Eng-Tjioe (1999), "Chiungtze C. Tsen (1898–1940) and Tsen's theorems", Rocky Mountain Journal of Mathematics, 29 (4): 1237–1269, doi:10.1216/rmjm/1181070406, ISSN 0035-7596, MR 1743370

- Dieudonné, Jean A.; Carrell, James B. (1970), "Invariant theory, old and new", Advances in Mathematics, 4 (1): 1–80, doi:10.1016/0001-8708(70)90015-0, ISSN 0001-8708, MR 0255525

- Dörnte, Wilhelm (1929), "Untersuchungen über einen verallgemeinerten Gruppenbegriff" [Investigations on a generalised conception of groups], Mathematische Zeitschrift (in الألمانية), 29 (1): 1–19, doi:10.1007/BF01180515

- Falckenberg, Hans (1912), Verzweigungen von Lösungen nichtlinearer Differentialgleichungen [Ramifications of Solutions of Nonlinear Differential Equations] (PhD thesis) (in الألمانية)

- Fitting, Hans (1933), "Die Theorie der Automorphismenringe Abelscher Gruppen und ihr Analogon bei nicht kommutativen Gruppen" [The Theory of Automorphism-Rings of Abelian Groups and Their Analogs in Noncommutative Groups], Mathematische Annalen (in الألمانية), 107 (1): 514–542, doi:10.1007/BF01448909

- Fleischmann, Peter (2000), "The Noether bound in invariant theory of finite groups", Advances in Mathematics, 156 (1): 23–32, doi:10.1006/aima.2000.1952, MR 1800251

- Fogarty, John (2001), "On Noether's bound for polynomial invariants of a finite group", Electronic Research Announcements of the American Mathematical Society, 7 (2): 5–7, doi:10.1090/S1079-6762-01-00088-9, MR 1826990

- Gilmer, Robert (1981), "Commutative Ring Theory", in Brewer, James W.; Smith, Martha K. (eds.), Emmy Noether: A Tribute to Her Life and Work, New York: Marcel Dekker, pp. 131–143, ISBN 978-0-8247-1550-2

- Givant, Steven; Halmos, Paul Richard (2009), Introduction to Boolean Algebras, Springer, ISBN 978-0-387-40293-2

- Goodearl, Ken R.; Warfield Jr., R. B. (2004), An Introduction to Noncommutative Noetherian Rings, London Mathematical Society Student Texts (2nd ed.), Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-511-21192-8

- Gordan, Paul (1870), "Die simultanen Systeme binärer Formen", Mathematische Annalen (in الألمانية), 2 (2): 227–280, doi:10.1007/BF01444021, S2CID 119558943, archived from the original on 3 September 2014

- Gowers, Timothy; Barrow-Green, June; Leader, Imre, eds. (2008), The Princeton Companion to Mathematics, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-11880-2

- Gray, Jeremy (2018), A History of Abstract Algebra, Springer Undergraduate Mathematics Series, Springer, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-94773-0, ISBN 978-3-319-94772-3

- Grell, Heinrich (1927), "Beziehungen zwischen den Idealen verschiedener Ringe" [Relationships between the Ideals of Various Rings], Mathematische Annalen (in الألمانية), 97 (1): 490–523, doi:10.1007/BF01447879

- Haboush, William J. (1975), "Reductive groups are geometrically reductive", Annals of Mathematics, 102 (1): 67–83, doi:10.2307/1970974, JSTOR 1970974

- Hasse, Helmut (1933), "Die Struktur der R. Brauerschen Algebrenklassengruppe über einem algebraischen Zahlkörper", Mathematische Annalen (in الألمانية), 107 (1): 731–760, doi:10.1007/BF01448916, S2CID 128305900, archived from the original on 5 March 2016

- Hartshorne, Robin (1977), Algebraic Geometry, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-0-387-90244-9, MR 0463157, Zbl 0367.14001

- Hermann, Grete (1926), "Die Frage der endlich vielen Schritte in der Theorie der Polynomideale. (Unter Benutzung nachgelassener Sätze von K. Hentzelt)" [The Question of the Finite Number of Steps in the Theory of Ideals of Polynomials. (Using Theorems of the Late Kurt Hentzelt)], Mathematische Annalen (in الألمانية), 95 (1): 736–788, doi:10.1007/BF01206635

- Hilbert, David (December 1890), "Ueber die Theorie der algebraischen Formen", Mathematische Annalen (in الألمانية), 36 (4): 473–534, doi:10.1007/BF01208503, S2CID 179177713, archived from the original on 3 September 2014

- Hilton, Peter (1988), "A Brief, Subjective History of Homology and Homotopy Theory in this Century", Mathematics Magazine, 60 (5): 282–291, doi:10.1080/0025570X.1988.11977391, JSTOR 2689545

- Hölzer, Rudolf (1927), "Zur Theorie der primären Ringe" [On the Theory of Primary Rings], Mathematische Annalen (in الألمانية), 96 (1): 719–735, doi:10.1007/BF01209197

- Hopf, Heinz (1928), "Eine Verallgemeinerung der Euler-Poincaréschen Formel", Nachrichten von der Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen. Mathematisch-Physikalische Klasse (in الألمانية), 2: 127–136

- Hubbard, John H.; West, Beverly H. (1991), Differential Equations: A Dynamical Systems Approach. Part II: Higher-Dimensional Systems, Texts in Applied Mathematics, vol. 5, Springer, ISBN 978-0-38-794377-0

- James, Ioan (2002), "Emmy Noether (1882–1935)", Remarkable Mathematicians from Euler to von Neumann, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 321–326, ISBN 978-0-521-81777-6

- Kimberling, Clark (1981), "Emmy Noether and Her Influence", in Brewer, James W.; Smith, Martha K. (eds.), Emmy Noether: A Tribute to Her Life and Work, New York: Marcel Dekker, pp. 3–61, ISBN 978-0-8247-1550-2

- Kimberling, Clark (March 1982), "Emmy Noether, Greatest Woman Mathematician" (PDF), Mathematics Teacher, Reston, Virginia: National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, 84 (3): 246–249, doi:10.5951/MT.75.3.0246

- Kosmann-Schwarzbach, Yvette (2011), The Noether Theorems: Invariance and Conservation Laws in the Twentieth Century, Sources and Studies in the History of Mathematics and Physical Sciences, translated by Schwarzbach, Bertram Eugene, Springer, doi:10.1007/978-0-387-87868-3, ISBN 978-0-387-87867-6

- Lam, Tsit Yuen (1981), "Representation Theory", in Brewer, James W.; Smith, Martha K. (eds.), Emmy Noether: A Tribute to Her Life and Work, New York: Marcel Dekker, pp. 145–156, ISBN 978-0-8247-1550-2

- Lang, Serge (2002), Algebra (3rd ed.), Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-1-4613-0041-0

- Lang, Serge (2005), Undergraduate Algebra (3rd ed.), Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-0-387-22025-3

- Lederman, Leon M.; Hill, Christopher T. (2004), Symmetry and the Beautiful Universe, Amherst: Prometheus Books, ISBN 978-1-59102-242-8

- Levitzki, Jakob (1931), "Über vollständig reduzible Ringe und Unterringe" [On Completely Reducible Rings and Subrings], Mathematische Zeitschrift (in الألمانية), 33 (1): 663–691, doi:10.1007/BF01174374

- Mac Lane, Saunders (1981), "Mathematics at the University of Göttingen 1831–1933", in Brewer, James W.; Smith, Martha K. (eds.), Emmy Noether: A Tribute to Her Life and Work, New York: Marcel Dekker, pp. 65–78, ISBN 978-0-8247-1550-2

- Malle, Gunter; Matzat, Bernd Heinrich (1999), Inverse Galois theory, Springer Monographs in Mathematics, Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-3-540-62890-3, https://archive.org/details/inversegaloisthe0000mall

- Merzbach, Uta C. (1983), "Emmy Noether: Historical Contexts", in Srinivasan, Bhama; Sally, Judith D. (eds.), Emmy Noether in Bryn Mawr: Proceedings of a Symposium Sponsored by the Association for Women in Mathematics in Honor of Emmy Noether's 100th Birthday, New York, NY: Springer, pp. 161–171, doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-5547-5_12, ISBN 978-1-4612-5547-5

- McLarty, Colin (2005), "Poor Taste as a Bright Character Trait: Emmy Noether and the Independent Social Democratic Party" (PDF), Science in Context, 18 (3): 429–450, doi:10.1017/S0269889705000608

- Noether, Gottfried E. (1987), Grinstein, L.S.; Campbell, P.J. (eds.), Women of Mathematics, New York: Greenwood Press, ISBN 978-0-313-24849-8

- Noether, Max (1914), "Paul Gordan", Mathematische Annalen, 75 (1): 1–41, doi:10.1007/BF01564521, S2CID 179178051, archived from the original on 4 September 2014

- Ogilvie, Marilyn; Harvey, Joy (2000), The Biographical Dictionary of Women in Science: Pioneering Lives from Ancient Times to the Mid-Twentieth Century, vol. 2 (L–Z), New York and London: Routledge, ISBN 978-0-2038-0145-1

- Osofsky, Barbara L. (1994), "Noether Lasker Primary Decomposition Revisited", The American Mathematical Monthly, 101 (8): 759–768, doi:10.1080/00029890.1994.11997022

- Peres, Asher (1993), Quantum Theory: Concepts and Methods, Kluwer, ISBN 0-7923-2549-4

- Reid, Constance (1996), Hilbert, New York: Springer, ISBN 0-387-94674-8

- Roquette, Peter (2005), The Brauer–Hasse–Noether theorem in historical perspective, Schriften der Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Klasse der Heidelberger Akademie der Wissenschaften, vol. 15, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.72.4101, MR 2222818, Zbl 1060.01009

- Rowe, David E. (2021), Emmy Noether – Mathematician Extraordinaire, Cham, Switzerland: Springer, ISBN 978-3-030-63810-8

- Rowe, David E.; Koreuber, Mechthild (2020), Proving It Her Way: Emmy Noether, a Life in Mathematics, Cham, Switzerland: Springer, ISBN 978-3-030-62811-6

- Schmadel, Lutz D. (2003), Dictionary of Minor Planet Names (5th revised and enlarged ed.), Berlin: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-3-540-00238-3

- Schur, Issai (1968), Grunsky, Helmut (ed.), Vorlesungen über Invariantentheorie, Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-3-540-04139-9, MR 0229674

- Segal, Sanford L. (2003), Mathematicians Under the Nazis (illustrated ed.), Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-69-100451-8

- Seidelmann, Fritz (1917), "Die Gesamtheit der kubischen und biquadratischen Gleichungen mit Affekt bei beliebigem Rationalitätsbereich" [Complete Set of Cubic and Biquadratic Equations with Affect in an Arbitrary Rationality Domain], Mathematische Annalen (in الألمانية), 78 (1–4): 230–233, doi:10.1007/BF01457100, hdl:2027/uc1.b2611861

- Schilling, Otto (1935), "Über gewisse Beziehungen zwischen der Arithmetik hyperkomplexer Zahlsysteme und algebraischer Zahlkörper" [On Certain Relationships between the Arithmetic of Hypercomplex Number Systems and Algebraic Number Fields], Mathematische Annalen (in الألمانية), 111 (1): 372–398, doi:10.1007/BF01472227

- Stauffer, Ruth (July 1936), "The Construction of a Normal Basis in a Separable Normal Extension Field", American Journal of Mathematics, 58 (3): 585–597, doi:10.2307/2370977, JSTOR 2370977

- Stewart, Ian (2015), Galois Theory (4th ed.), CRC Press, ISBN 978-1-4822-4582-0

- Swan, Richard G (1969), "Invariant rational functions and a problem of Steenrod", Inventiones Mathematicae, 7 (2): 148–158, Bibcode:1969InMat...7..148S, doi:10.1007/BF01389798, S2CID 121951942

- Taussky, Olga (1981), "My Personal Recollections of Emmy Noether", in Brewer, James W.; Smith, Martha K (eds.), Emmy Noether: A Tribute to Her Life and Work, New York: Marcel Dekker, pp. 79–92, ISBN 978-0-8247-1550-2

- Taylor, John R. (2005), Classical Mechanics, University Science Books, ISBN 978-1-8913-8922-1