هارولد ماكميلان

| المبجل The Earl of Stockton OM، مجلس الخاصة | |

|---|---|

| |

| Official portrait, 1959 | |

| رئيس وزراء المملكة المتحدة | |

| في المنصب 10 يناير 1957 – 18 أكتوبر 1963 | |

| العاهل | إليزابث الثانية |

| نائب | راب بوتلر |

| سبقه | سير أنطوني إيدن |

| خلفه | سير ألكس دوگلاس هوم |

| وزير طيران | |

| في المنصب 25 مايو – 26 يوليو 1945 | |

| رئيس الوزراء | ونستون تشرشل (حكومة تسيير أعمال) |

| سبقه | Sir Archibald Sinclair |

| خلفه | The Viscount Stansgate |

| وزير الإسكان والحكومة المحلية | |

| في المنصب 30 أكتوبر 1951 – 19 أكتوبر 1954 | |

| رئيس الوزراء | ونستون تشرشل |

| سبقه | منصب جديد Hugh Dalton had been Minister of Local Government & Planning |

| خلفه | Duncan Sandys |

| وزير الدفاع | |

| في المنصب 19 أكتوبر 1954 – 7 أبريل 1955 | |

| رئيس الوزراء | ونستون تشرشل |

| سبقه | The Earl Alexander of Tunis |

| خلفه | Selwyn Lloyd |

| وزير الخارجية | |

| في المنصب 7 أبريل – 20 December 1955 | |

| رئيس الوزراء | سير أنطوني إيدن |

| سبقه | سير أنطوني إيدن |

| خلفه | Selwyn Lloyd |

| Chancellor of the Exchequer | |

| في المنصب 20 ديسمبر 1955 – 13 يناير 1957 | |

| رئيس الوزراء | سير أنطوني إيدن |

| سبقه | Rab Butler |

| خلفه | Peter Thorneycroft |

| تفاصيل شخصية | |

| وُلِد | 10 فبراير 1894 تشلسا، لندن، المملكة المتحدة |

| توفي | 29 ديسمبر 1986 Chelwood Gate, Sussex، المملكة المتحدة |

| القومية | بريطاني |

| الحزب | المملكة المتخحدة |

| الزوج | ليدي دروثي ماكميلان |

| الجامعة الأم | Balliol College, Oxford |

| المهنة | ناشر |

| الدين | أنجليكاني [1] |

هارولد ماكميلان (و. (10 فبراير 1894 – 29 ديسمبر 1986) هو رئيس وزراء المملكة المتحدة عن حزب المحافظين من 10 يناير 1957 إلى 18 أكتوبر 1963.[2] Nicknamed "Supermac", he was known for his pragmatism, wit, and unflappability.

Macmillan was seriously injured as an infantry officer during the First World War. He suffered pain and partial immobility for the rest of his life. After the war he joined his family book-publishing business, then entered Parliament at the 1924 general election for Stockton-on-Tees. Losing his seat in 1929, he regained it in 1931, soon after which he spoke out against the high rate of unemployment in Stockton. He opposed the appeasement of Germany practised by the Conservative government. He rose to high office during the Second World War as a protégé of Prime Minister Winston Churchill. In the 1950s Macmillan served as Foreign Secretary and Chancellor of the Exchequer under Anthony Eden.

When Eden resigned in 1957 following the Suez Crisis, Macmillan succeeded him as prime minister and Leader of the Conservative Party. He was a One Nation Tory of the Disraelian tradition and supported the post-war consensus. He supported the welfare state and the necessity of a mixed economy with some nationalised industries and strong trade unions. He championed a Keynesian strategy of deficit spending to maintain demand and pursuit of corporatist policies to develop the domestic market as the engine of growth. Benefiting from favourable international conditions,[3] he presided over an age of affluence, marked by low unemployment and high—if uneven—growth. In his speech of July 1957 he told the nation it had "never had it so good",[4] but warned of the dangers of inflation, summing up the fragile prosperity of the 1950s. [5] He led the Conservatives to success in 1959 with an increased majority.

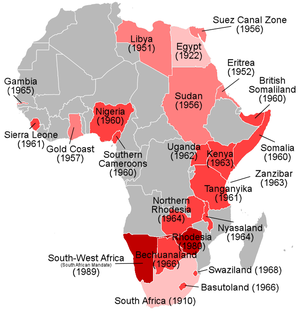

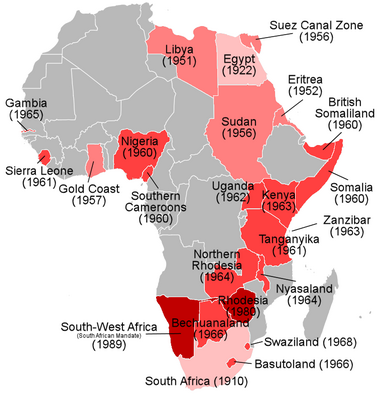

In international affairs, Macmillan worked to rebuild the Special Relationship with the United States from the wreckage of the 1956 Suez Crisis (of which he had been one of the architects), and facilitated the decolonisation of Africa. Reconfiguring the nation's defences to meet the realities of the nuclear age, he ended National Service, strengthened the nuclear forces by acquiring Polaris, and pioneered the Nuclear Test Ban with the United States and the Soviet Union. After the Skybolt Crisis undermined the Anglo-American strategic relationship, he sought a more active role for Britain in Europe, but his unwillingness to disclose United States nuclear secrets to France contributed to a French veto of the United Kingdom's entry into the European Economic Community and independent French acquisition of nuclear weapons in 1960.[6] ظل في منصبه حتى استقال في عام 1963 بعد فضيحة جون بروفومو وزير البحرية البريطانية بعد ثبوت تورطه في علاقة غير شرعية مع كريستين كير التي كانت تتجسس لحساب الاتحاد السوفيتي.[7] Following his resignation, Macmillan lived out a long retirement as an elder statesman, being an active member of the House of Lords in his final years. He died in December 1986 at the age of 92.

النشأة

ولد ماكميلان في 10 فبراير 1894 في لندن، وكان أصغر أخوته الثلاث. تعلم في مدرسة إيتون وكلية باليون بجامعة أكسفورد. دخل البرلمان لأول مرة في: 29 أكتوبر 1924. شغل منصب رئيس الوزراء لأكثر من ستة أعوام. لقب ب"سوبرماك" و"ماك السكين". تزوج من دوروثي كافيندش وأنجب إبن وثلاث بنات. كان مهتما بالأدب وصيد الأماك والجولف والكريكيت.[8]

كان هارولد مكميلان نصف أمريكي بالمولد، وهو ابن ناشر نشأت أسرته من خلفية متواضعة. وُلد مكميلان في تشيلسي وتلقى تعليمه في مدرسة إيتون وكلية باليول بجامعة أكسفورد، حيث أبدى تميزه الدراسي هناك.

أصيب ثلاث مرات أثناء خدمته في الجيش خلال الحرب العالمية الأولى.

السيرة السياسية، 1924-1951

عضو مجلس النواب (1924–1929)

عمل في شركة النشر التي تمتلكها عائلته لبعض الوقت قبل أن يُنتخب عوضا في البرلمان لحزب المحافظين عن دائرة ستوكون أون تيز - وهي بلدة صناعية كئيبة. كان للحالة المزرية للمنطقة والصعوبات الاقتصادية التي يواجهها أهلها تأثير عميق عليه. وخلال حياته البرلمانية المبكرة كان عضوا في فريق الجناح الأيسر ضمن الحزب، وهو فريق مارس الضغوط تجاه الإصلاح الاجتماعي.

وخلال عامي 1936-1937 استقال من منصبه حين كان مسؤولا عن تصويت الأعضاء في البرلمان لكي يكتب "الطريق الوسط" الذي حدد معتقداته الوسطية في حزب المحافظين. تعيَّن مكميلان بمنصب وزير دولة عام 1940، وفي عام 1942 أصبح وزيرا مقيما في مقر القوات المشتركة في البحر الأبيض المتوسط، حيث أصبح هناك صديقا للجنرال آيزنهاور.

خسر مكميلان مقعده عام 1945، لكنه عاد وفاز به بعد فترة قصيرة في الانتخابات التكميلية التي جرت في بروملي. وقد مثل الحزب المعارض حتى عام 1951، حيث كان مسؤولا عن المسائل الاقتصادية والصناعية.

ولدى فوز حزب المحافظين بالانتخابات عام 1951، انضم مكميلان لمجلس الوزراء بمنصب وزير الإسكان. وقد برهن على كونه وزيرا فعالا، حيث أشرف على بناء مليون منزل جديد تقريبا. وفي عام 1954 تولى منصب وزير الدفاع، ثم عينه آنتوني إيدن وزيرا للخارجية في عام 1955.

وزير الخزانة (1955–1957)

إلا أن إيدن أراد شخصيا السيطرة على الشؤون الخارجية، وبعد تسعة شهور نقل مكميلان ضد رغبته ليصبح وزيرا للخزانة. أيد مكميلان مبدئيا الإجراء الذي اتخذه إيدن بشأن أزمة السويس، لكنه غيَّر موقفه لاحقا.

بعد استقالة إيدن، وعلى الرغم من التكهنات الواسعة النطاق بأن يتولى راب بتلر منصب رئيس الوزراء خلفا لإيدن، دعت الملكة مكميلان لتشكيل الحكومة. وقد توقع مكميلان شخصيا بأن تكون ولايته قصيرة الأمد. لكن عوضا عن ذلك حقق نجاحا كبيرا في إحياء المعنويات والثقة لدى كل من الحزب وعلى المستوى الوطني.

الميزانية

Macmillan was appointed Chancellor of the Exchequer in December 1955.[9] He had enjoyed his eight months as Foreign Secretary and did not wish to move. He insisted on being "undisputed head of the home front" and that Eden's de facto deputy Rab Butler, whom he was replacing as Chancellor, not have the title "Deputy Prime Minister" and not be treated as senior to him. He even tried (in vain) to demand that Salisbury, not Butler, should preside over the Cabinet in Eden's absence. Macmillan later claimed in his memoirs that he had still expected Butler, his junior by eight years, to succeed Eden, but correspondence with Lord Woolton at the time makes clear that Macmillan was very much thinking of the succession. As early as January 1956 he told Eden's press secretary William D. Clark that it would be "interesting to see how long Anthony can stay in the saddle".[10]

Macmillan planned to reverse the 6d cut in income tax which Butler had made a year previously, but backed off after a "frank talk" with Butler, who threatened resignation, on 28 March 1956. He settled for spending cuts instead, and himself threatened resignation until he was allowed to cut bread and milk subsidies, something the Cabinet had not permitted Butler to do.[11]

One of his innovations at the Treasury was the introduction of premium bonds,[12] announced in his budget of 17 April 1956.[13] Although the Labour Opposition initially decried them as a 'squalid raffle', they proved an immediate hit with the public, with £1,000 won in the first prize draw in June 1957.

A young John Major attended the presentation of the budget, and attributes his political ambitions to this event.[14]

أزمة السويس

In November 1956, Britain invaded Egypt in collusion with France and Israel in the Suez Crisis. According to Labour Shadow Chancellor Harold Wilson, Macmillan was 'first in, first out':[15] first very supportive of the invasion, then a prime mover in Britain's humiliating withdrawal in the wake of the financial crisis caused by pressure from the US government.[16] Since the Egyptian Revolution of 1952, relations between Britain and Egypt had deteriorated. The Egyptian government, which came to be dominated by Gamal Abdel Nasser, was opposed to the British military presence in the Arab World. The Egyptian nationalisation of the Suez Canal by Nasser on 26 July 1956 prompted the British government and the French government of Guy Mollet to commence plans for invading Egypt, regaining the canal, and toppling Nasser. Macmillan wrote in his diary: "If Nasser 'gets away with it', we are done for. The whole Arab world will despise us ... Nuri [es-Said, British-backed Prime Minister of Iraq] and our friends will fall. It may well be the end of British influence and strength forever. So, in the last resort, we must use force and defy opinion, here and overseas".[17]

Macmillan threatened to resign if force was not used against Nasser.[18] He was heavily involved in the secret planning of the invasion with France and Israel. It was he who first suggested collusion with Israel.[19] On 5 August 1956 Macmillan met Churchill at Chartwell, and told him that the government's plan for simply regaining control of the canal was not enough and suggested involving Israel, recording in his diary for that day: "Surely, if we landed we must seek out the Egyptian forces; destroy them; and bring down Nasser's government. Churchill seemed to agree with all this."[20] Macmillan knew President Eisenhower well, but misjudged his strong opposition to a military solution. Macmillan met Eisenhower privately on 25 September 1956 and convinced himself that the US would not oppose the invasion,[21] despite the misgivings of the British Ambassador, Sir Roger Makins, who was also present. Macmillan failed to heed a warning from Secretary of State John Foster Dulles that whatever the British government did should wait until after the US presidential election on 6 November, and failed to report Dulles' remarks to Eden.

The treasury was his portfolio, but he did not recognise the financial disaster that could result from US government actions. Sterling was draining out of the Bank of England at an alarming rate. The canal was blocked by the Egyptians, and most oil shipments were delayed as tankers had to go around Africa. The US government refused any financial help until Britain withdrew its forces from Egypt. When he did realise this, he changed his mind and called for withdrawal on US terms, while exaggerating the financial crisis.[22] On 6 November Macmillan informed the Cabinet that Britain had lost $370m in the first few days of November alone.[23] Faced with Macmillan's prediction of doom, the cabinet had no choice but to accept these terms and withdraw. The Canal remained in Egyptian hands, and Nasser's government continued its support of Arab and African national resistance movements opposed to the British and French presence in the region and on the continent.[22]

In later life Macmillan was open about his failure to read Eisenhower's thoughts correctly and much regretted the damage done to Anglo-American relations, but always maintained that the Anglo-French military response to the nationalisation of the Canal had been for the best.[24] D. R. Thorpe rejects the charge that Macmillan deliberately played false over Suez (i.e. encouraged Eden to attack in order to destroy him as prime minister), noting that Macmillan privately put the chances of success at 51–49.[25]

خلافة إيدن

Britain's humiliation at the hands of the US caused deep anger among Conservative MPs. After the ceasefire a motion on the Order Paper attacking the US for "gravely endangering the Atlantic Alliance" attracted the signatures of over a hundred MPs.[26] Macmillan tried, but failed, to see Eisenhower (who was also refusing to see Foreign Secretary Selwyn Lloyd) behind Butler's and Eden's back. Macmillan had a number of meetings with US Ambassador Winthrop Aldrich, in which he said that if he were prime minister the US Administration would find him much more amenable. Eisenhower encouraged Aldrich to have further meetings. Macmillan and Butler met Aldrich on 21 November. Eisenhower spoke highly of Macmillan ("A straight, fine man, and so far as he is concerned, the outstanding one of the British he served with during the war").[27][28]

On the evening of 22 November 1956 Butler, who had just announced British withdrawal, addressed the 1922 Committee (Conservative backbenchers) with Macmillan. After Butler's downbeat remarks, ten minutes or so in length, Macmillan delivered a stirring 35-minute speech described by Enoch Powell as "one of the most horrible things that I remember in politics ... (Macmillan) with all the skill of the old actor manager succeeded in false-footing Rab. The sheer devilry of it verged upon the disgusting." He expounded on his metaphor that henceforth the British must aim to be "Greeks in the Roman Empire", and according to Philip Goodhart's recollection almost knocked Butler off his chair with his expansive arm gestures. Macmillan wrote "I held the Tory Party for the weekend, it was all I intended to do". Macmillan had further meetings with Aldrich and Winston Churchill after Eden left for Jamaica (23 November) while briefing journalists (disingenuously) that he planned to retire and go to the Lords.[29][30] He was also hinting that he would not serve under Butler.[31]

Butler later recorded that during his period as acting Head of Government at Number 10, he noticed constant comings and goings of ministers to Macmillan's study in Number 11 next door, and that those who attended all seemed to receive promotions when Macmillan became prime minister. Macmillan had opposed Eden's trip to Jamaica and told Butler (15 December, the day after Eden's return) that younger members of the Cabinet wanted Eden out.[32] Macmillan argued at Cabinet on 4 January that Suez should be regarded as a "strategic retreat" like Mons or Dunkirk. This did not meet with Eden's approval at Cabinet on 7 January.[33]

His political standing destroyed, Eden resigned on grounds of ill health on 9 January 1957.[34] At that time the Conservative Party had no formal mechanism for selecting a new leader, and Queen Elizabeth II appointed Macmillan Prime Minister after taking advice from Churchill and the Marquess of Salisbury, who had asked the Cabinet individually for their opinions, all but two or three opting for Macmillan. This surprised some observers who had expected that Eden's deputy Rab Butler would be chosen.[35] The political situation after Suez was so desperate that on taking office on 10 January he told the Queen he could not guarantee his government would last "six weeks", though ultimately he would be in charge of the government for more than six years.[36]

Prime Minister (1957–1963)

| |

Premiership of Harold Macmillan | |

|---|---|

| 10 January 1957 – 18 October 1963 | |

| Elizabeth II | |

| رئيس الوزراء | Harold Macmillan |

| مجلس الوزراء | Macmillan ministry |

| الحزب | Conservative |

| الانتخابات | 1959 |

| المجلس | 10 Downing Street |

First government, 1957–1959

ساد خلال ولاية مكميلان مرحلة من الرخاء وتهدئة العلاقات إبان الحرب الباردة على الساحة الدولية.

From the start of his premiership, Macmillan set out to portray an image of calm and style, in contrast to his excitable predecessor. He silenced the klaxon on the Prime Ministerial car, which Eden had used frequently. He advertised his love of reading Anthony Trollope and Jane Austen, and on the door of the Private Secretaries' room at Number Ten he hung a quote from The Gondoliers: "Quiet, calm deliberation disentangles every knot".[37]

Macmillan filled government posts with 35 Old Etonians, seven of them in Cabinet.[38] He was also devoted to family members: when Andrew Cavendish, 11th Duke of Devonshire was later appointed (Minister for Colonial Affairs from 1963 to 1964 among other positions) he described his uncle's behaviour as "the greatest act of nepotism ever".[39] Macmillan's Defence Minister, Duncan Sandys, wrote at the time: "Eden had no gift for leadership; under Macmillan as PM everything is better, Cabinet meetings are quite transformed".[40] Many ministers found Macmillan to be more decisive and brisk than either Churchill or Eden had been.[40] Another of Macmillan's ministers, Charles Hill, stated that Macmillan dominated Cabinet meetings "by sheer superiority of mind and of judgement".[41] Macmillan frequently made allusions to history, literature and the classics at cabinet meetings, giving him a reputation as being both learned and entertaining, though many ministers found his manner too authoritarian.[41] Macmillan had no "inner cabinet", and instead maintained one-on-one relationships with a few senior ministers such as Rab Butler who usually served as acting prime minister when Macmillan was on one of his frequent visits abroad.[41] Selwyn Lloyd described Macmillan as treating most of his ministers like "junior officers in a unit he commanded".[41] Lloyd recalled that Macmillan: "regarded the Cabinet as an instrument to play upon, a body to be molded to his will...very rarely did he fail to get his way"[41] Macmillan generally allowed his ministers much leeway in managing their portfolios, and only intervened if he felt something had gone wrong.[40] Macmillan was especially close to his three private secretaries, Tom Bligh, Freddie Bishop and Philip de Zulueta, who were his favourite advisers.[41] Many cabinet ministers often complained that Macmillan took the advice of his private secretaries more seriously than he did their own.[41]

He was nicknamed "Supermac" in 1958 by the cartoonist Victor Weisz, who intended to suggest that Macmillan was trying set himself up as a "Superman" figure.[41] It was intended as mockery but backfired, coming to be used in a neutral or friendly fashion. Weisz tried to label him with other names, including "Mac the Knife" at the time of widespread cabinet changes in 1962, but none caught on.[42]

Economy

Besides foreign affairs, the economy was Macmillan's other prime concern.[43] His One Nation approach to the economy was to seek high or full employment, especially with a general election looming. This contrasted with the Treasury ministers who argued that support of sterling required spending cuts and, probably, a rise in unemployment. Their advice was rejected and in January 1958 the three Treasury ministers — Peter Thorneycroft, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Nigel Birch, Economic Secretary to the Treasury, and Enoch Powell, the Financial Secretary to the Treasury and seen as their intellectual ringleader — resigned. D. R. Thorpe argues that this, coming after the resignations of Labour ministers Aneurin Bevan, John Freeman and Harold Wilson in April 1951 (who had wanted higher expenditure), and the cuts made by Butler and Macmillan as Chancellors in 1955–56, was another step in the development of "stop-go" economics, as opposed to prudent medium-term management.[44] Macmillan, away on a tour of the Commonwealth, brushed aside this incident as "a little local difficulty". He bore no grudge against Thorneycroft and brought him and Powell, of whom he was more wary, back into the government in 1960.[45]

This period also saw the first stirrings of more active monetary policy. Official bank rate, which had been kept low since the 1930s, was hiked in September 1958.[44] The change in bank rate prompted rumours in the City that some financiers – who were Bank of England directors with senior positions in private firms – took advantage of advance knowledge of the rate change in what resembled insider trading. Political pressure mounted on the Government, and Macmillan agreed to the 1957 Bank Rate Tribunal. Hearing evidence in the winter of 1957 and reporting in January 1958, this inquiry exonerated all involved in what some journalists perceived to be a whitewash.[46]

Domestic policies

During his time as prime minister, average living standards steadily rose[47] while numerous social reforms were carried out. The Clean Air Act 1956 was passed during his time as Chancellor; his premiership saw the passage of the Housing Act 1957, the Offices Act 1960, the Noise Abatement Act 1960,[48] and the Factories Act 1961; the introduction of a graduated pension scheme to provide an additional income to retirees,[49] the establishment of a Child's Special Allowance for the orphaned children of divorced parents,[50] and a reduction in the standard work week from 48 to 42 hours.[51][صفحة مطلوبة]

Foreign policy

Macmillan took close control of foreign policy. He worked to narrow the post-Suez Crisis (1956) rift with the United States, where his wartime friendship with Eisenhower was key; the two had a productive conference in Bermuda as early as March 1957.

In February 1959, Macmillan visited the Soviet Union. Talks with Nikita Khrushchev eased tensions in east–west relations over West Berlin and led to an agreement in principle to stop nuclear tests and to hold a further summit meeting of Allied and Soviet heads of government.[52]

In the Middle East, faced by the 1958 collapse of the Baghdad Pact and the spread of Soviet influence, Macmillan acted decisively to restore the confidence of Persian Gulf allies, using the Royal Air Force and special forces to defeat a revolt backed by Saudi Arabia and Egypt against the Sultan of Oman, Said bin Taimur, in July 1957;[53] deploying airborne battalions to defend Jordan against United Arab Republican subversion in July 1958;[54] and deterring Iraqi demands of Kuwait by landing a brigade group in June 1961 during the Iraq–Kuwait crisis of 1961 .[55]

Macmillan was a major proponent and architect of decolonisation. The Gold Coast was granted independence as Ghana, and the Federation of Malaya achieved independence within the Commonwealth of Nations in 1957. "The material strength of the Old Commonwealth members, if joined with the moral influence of the Asiatic members, meant that a united Commonwealth would always have a very powerful voice in world affairs," said Macmillan in a 1957 speech during a tour of the former British Empire.[56]

Nuclear weapons

In April 1957, Macmillan reaffirmed his strong support for the British nuclear weapons programme. A succession of prime ministers since the Second World War had been determined to persuade the United States to revive wartime co-operation in the area of nuclear weapons research. Macmillan believed that one way to encourage such co-operation would be for the United Kingdom to speed up the development of its own hydrogen bomb, which was successfully tested on 8 November 1957.

Macmillan's decision led to increased demands on the Windscale and (subsequently) Calder Hall nuclear plants to produce plutonium for military purposes.[57] As a result, safety margins for radioactive materials inside the Windscale reactor were eroded. This contributed to the Windscale fire on the night of 10 October 1957, which broke out in the plutonium plant of Pile No. 1, and nuclear contaminants travelled up a chimney where the filters blocked some, but not all, of the contaminated material. The radioactive cloud spread to south-east England and fallout reached mainland Europe. Although scientists had warned of the dangers of such an accident for some time, the government blamed the workers who had put out the fire for 'an error of judgement', rather than the political pressure for fast-tracking the megaton bomb.[58][59]

Concerned that public confidence in the nuclear programme might be shaken and that technical information might be misused by opponents of defence co-operation in the US Congress, Macmillan withheld all but the summary of a report into the fire prepared for the Atomic Energy Authority by Sir William Penney, director of the Atomic Weapons Research Establishment.[60] Subsequently released files show that 'Macmillan's cuts were few and covered up few technical details',[61] and that even the full report found no danger to public health, but later official estimates acknowledged that the release of polonium-210 may have led directly to 25 to 50 deaths, and anti-nuclear groups linked it to 1,000 fatal cancers.[62][63]

On 25 March 1957, Macmillan acceded to Eisenhower's request to base 60 Thor IRBMs in England under joint control to replace the nuclear bombers of the Strategic Air Command, which had been stationed under joint control since 1948 and were approaching obsolescence. Partly as a consequence of this favour, in late October 1957 the US McMahon Act was eased to facilitate nuclear co-operation between the two governments, initially with a view to producing cleaner weapons and reducing the need for duplicate testing.[64] The Mutual Defence Agreement followed on 3 July 1958, speeding up British ballistic missile development,[65] notwithstanding unease expressed at the time about the impetus co-operation might give to atomic proliferation by arousing the jealousy of France and other allies.[66]

Macmillan saw an opportunity to increase British influence over the United States with the launching of the Soviet satellite Sputnik, which caused a severe crisis of confidence in the United States as Macmillan wrote in his diary: "The Russian success in launching the satellite has been something equivalent to Pearl Harbour. The American cockiness is shaken....President is under severe attack for the first time...The atmosphere is now such that almost anything might be decided, however revolutionary".[67] The "revolutionary" change that Macmillan sought was a more equal Anglo-American partnership as he used the Sputnik crisis to press Eisenhower to in turn press Congress to repeal the 1946 MacMahon Act, which forbade the United States to share nuclear technology with foreign governments, a goal accomplished by the end of 1957.[68]

In addition, Macmillan succeeded in having Eisenhower to agree to set up Anglo-American "working groups" to examine foreign policy problems and for what he called the "Declaration of Interdependence" (a title not used by the Americans who called it the "Declaration of Common Purpose"), which he believed marked the beginning of a new era of Anglo-American partnership.[69] Subsequently, Macmillan was to learn that neither Eisenhower nor Kennedy shared the assumption that he applied to the "Declaration of Interdependence" that the American president and the British Prime Minister had equal power over the decisions of war and peace.[70] Macmillan believed that the American policies towards the Soviet Union were too rigid and confrontational, and favoured a policy of détente with the aim of relaxing Cold War tensions.[71]

1959 general election

Macmillan led the Conservatives to victory in the 1959 general election, increasing his party's majority from 60 to 100 seats. The campaign was based on the economic improvements achieved as well as the low unemployment and improving standard of living; the slogan "Life's Better Under the Conservatives" was matched by Macmillan's own 1957 remark, "indeed let us be frank about it—most of our people have never had it so good,"[72] usually paraphrased as "You've never had it so good." Such rhetoric reflected a new reality of working-class affluence; it has been argued that "the key factor in the Conservative victory was that average real pay for industrial workers had risen since Churchill's 1951 victory by over 20 per cent".[73] The scale of the victory meant that not only had the Conservatives won three successive general elections, but they had also increased their majority each time. It sparked debate as to whether Labour (now led by Hugh Gaitskell) could win a general election again. The standard of living had risen enough that workers could participate in a consumer economy, shifting the working class concerns away from traditional Labour Party views.[74]

كانت تلك هي الفترة التي لقب بها بكنية "سوبرماك"، وفي عام 1959 فاز بأغلبية مريحة في الانتخابات العامة.

الحكومة الثانية (1959-1963)

إلا أن ولايته الثانية لم تكن خالية تماما من المشاكل. فقد أدى تقدم بريطانيا بطلب عضويتها بالمجموعة الاقتصادية الأوروبية إلى حدوث انقسام في حزب المحافظين، وفي النهاية رفض شارل دو غول هذا الطلب.

وقد أثر التضخم والبطء في النمو على الاقتصاد، وتم اعتبار بأن مكميلان لم يُجد معالجة فضيحة بروفومو.

الاقتصاد

Britain's balance of payments problems led Chancellor Selwyn Lloyd to impose a seven-month wage freeze in 1961[75] and, amongst other factors, this caused the government to lose popularity and a series of by-elections in March 1962, of which the most famous was Orpington on 14 March.[76] Butler leaked to the Daily Mail on 11 July 1962 that a major reshuffle was imminent.[77] Macmillan feared for his own position and later (1 August) claimed to Lloyd that Butler, who sat for a rural East Anglian seat likely to suffer from EC agricultural protectionism, had been planning to split the party over EC entry (there is no evidence that this was so).[78]

In the 1962 cabinet reshuffle known as the "Night of the Long Knives", Macmillan sacked eight Ministers, including Selwyn Lloyd. The Cabinet changes were widely seen as a sign of panic, and the young Liberal MP Jeremy Thorpe said of Macmillan's dismissals, "greater love hath no man than this, than to lay down his friends for his life". Macmillan was openly criticised by his predecessor Lord Avon, an almost unprecedented act.[79]

Macmillan supported the creation of the National Economic Development Council (NEDC, known as "Neddy"), which was announced in the summer of 1961 and first met in 1962. However, the National Incomes Commission (NIC, known as "Nicky"), set up in October 1962 to institute controls on income as part of his growth-without-inflation policy, proved less effective. This was largely due to employers and the Trades Union Congress (TUC) boycotting it.[75] A further series of subtle indicators and controls was introduced during his premiership.

The report The Reshaping of British Railways[80] (or Beeching I report) was published on 27 March 1963. The report starts by quoting the brief provided by the prime minister, Harold Macmillan, from 1960, "First, the industry must be of a size and pattern suited to modern conditions and prospects. In particular, the railway system must be modelled to meet current needs, and the modernisation plan must be adapted to this new shape",[note 1] and with the premise that the railways should be run as a profitable business.[note 2] This led to the notorious Beeching Axe, destroying many miles of permanent way and severing towns from the railway network.

السياسة الخارجية

In the age of jet aircraft Macmillan travelled more than any previous prime minister, apart from Lloyd George who made many trips to conferences in 1919–22.[81] Macmillan planned an important role in setting up a four power summit in Paris to discuss the Berlin crisis that was supposed to open in May 1960, but which Khrushchev refused to attend owing to the U-2 incident.[82] Macmillan pressed Eisenhower to apologise to Khrushchev, which the president refused to do.[83] Macmillan's failure to make Eisenhower "say sorry" to Khrushchev forced him to reconsider his "Greeks and Romans" foreign policy as he privately conceded that could no "longer talk usefully to the Americans".[83] The failure of the Paris summit changed Macmillan's attitude towards the European Economic Community, which he started to see as a counterbalance to American power.[84] At the same time, the Anglo-American "working groups", which Macmillan attached such importance to turned out to be largely ineffective as the Americans did not wish to have their options limited by a British veto; by in-fighting between agencies of the U.S. government such as the State Department, Defense Department, etc.; and because of the Maclean-Burgess affair of 1951 the Americans believed the British government was full of Soviet spies and thus could not be trusted.[84]

Relations with the United States

The special relationship with the United States continued after the election of President John F. Kennedy, whose sister Kathleen Cavendish had married William Cavendish, Marquess of Hartington, the nephew of Macmillan's wife. Macmillan initially was concerned that the Irish-American Catholic Kennedy might be an Anglophobe, which led Macmillan, who knew of Kennedy's special interest in the Third World, to suggest that Britain and the United States spend more money on aid to the Third World.[85] The emphasis on aid to the Third World also coincided well with Macmillan's "one nation conservatism" as he wrote in a letter to Kennedy advocating reforms to capitalism to ensure full employment: "If we fail in this, Communism will triumph, not by war or even by subversion but by seemingly to be a better way of bringing people material comforts".[85]

Macmillan was scheduled to visit the United States in April 1961, but with the Pathet Lao winning a series of victories in the Laotian Civil War, Macmillan was summoned on what he called the "Laos dash" for an emergency summit with Kennedy in Key West on 26 March 1961.[86] Macmillan was strongly opposed to the idea of sending British troops to fight in Laos, but was afraid of damaging relations with the United States if he did not, making him very apprehensive as he set out for Key West, especially as he had never met Kennedy before.[87] Macmillan was especially opposed to intervention in Laos as he had been warned by his Chiefs of Staff on 4 January 1961 that if Western troops entered Laos, then China would probably intervene in Laos as Mao Zedong had made it quite clear he would not accept Western forces in any nation that bordered China.[88] The same report stated that a war with China in Laos would "be a bottomless pit in which our limited military resources would rapidly disappear".[88] Kennedy for his part wanted Britain to commit forces to Laos if the United States did for political reasons.[89] The meeting in Key West was very tense as Macmillan was heard to mutter "He's pushing me hard, but I won't give way".[87] However, Macmillan did reluctantly agree if the Americans intervened in Laos, then so too would Britain. The Laos crisis had a major crisis in Anglo-Thai relations as the Thais pressed for armed forces of all SEATO members to brought to "Charter Yellow", a state of heightened alert that the British representative to SEATO vetoed.[90] The Thais wanted to change the voting procedure for SEATO from requiring unanimous consent to a three-quarter majority, a measure that Britain vetoed, causing the Thais to lose interest in SEATO.[91]

The failure of the Bay of Pigs invasion in April 1961 made Kennedy distrust the hawkish advice he received from the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the CIA, and he ultimately decided against intervention in Laos, much to Macmillan's private relief. Macmillan's second meeting with Kennedy in April 1961 was friendlier and his third meeting in London in June 1961 after Kennedy had been bested by Khrushchev at a summit in Vienna even more so. It was at his third meeting in London that Macmillan started to assume the mantle of an elder statesman, who offered Kennedy encouragement and his experience that formed a lasting friendship.[92] Believing that personal diplomacy was the best way to influence Kennedy, Macmillan appointed David Ormsby-Gore as his ambassador in Washington as he was a long-time friend of the Kennedy family, whom he had known since the 1930s when Kennedy's father had served as the American ambassador in London.[93]

He was supportive throughout the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962 and Kennedy consulted him by telephone every day. The Ambassador David Ormsby-Gore was a close family friend of the president and actively involved in White House discussions on how to resolve the crisis.[94] About the Congo crisis, Macmillan clashed with Kennedy as he was against having United Nations forces put an end to the secessionist regime of Katanga backed by Belgium and the Western mining companies, which he claimed would destabilise the Central African Federation.[95] By contrast, Kennedy felt that the regime of Katanga was a Belgian puppet state and its mere existence was damaging to the prestige of the West in the Third World. Over Macmillan's objections, Kennedy decided to have the United Nations forces to evict the white mercenaries from Katanga and reintegrate Katanga into the Congo.[95] For his part, Kennedy pressed Macmillan unsuccessfully to have Britain join the American economic embargo against Cuba.[95] Macmillan told his Foreign Secretary, Lord Home "there is no reason for us to help the Americans with Cuba".[95]

Macmillan was a supporter of the nuclear test ban treaty of 1963, and in the first half of 1963 he had Ormsby-Gore quietly apply pressure on Kennedy to resume the talks in the spring of 1963 when negotiations became stalled. Feeling that the Secretary of State, Dean Rusk, was being obstructionist, Macmillan telephoned Kennedy on 11 April 1963 to suggest a joint letter to Khrushchev to break the impasse.[96] Though Khrushchev's reply to the Macmillan-Kennedy letter was mostly negative, Macmillan pressed Kennedy to take up the one positive aspect in his reply, namely that if a senior Anglo-American team would arrive in Moscow, he would welcome them to discuss how best to proceed about a nuclear test ban treaty.[96] The two envoys who arrived in Moscow were W. Averell Harriman representing the United States and Lord Hailsham representing the United Kingdom.[97] Though Lord Hailsham's role was largely that of an observer, the talks between Harriman and the Soviet foreign minister Andrei Gromyko resulted in the breakthrough that led to the Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty of August 1963, banning all above ground nuclear tests.[97] Macmillan had pressing domestic reasons for the nuclear test ban treaty. Newsreel footage of Soviet and American nuclear tests throughout the 1950s had terrified segments of the British public who were highly concerned about the possibility of weapons with such destructive power being used against British cities, and this led to the foundation of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND), whose rallies in the late 1950s-early 1960s calling for British nuclear disarmament were well attended. Macmillan believed in the value of nuclear weapons both as a deterrent against the Soviet Union and to maintain Britain's claim to be a great power, but he was also worried about the popularity of the CND.[98] For Macmillan, banning above-ground nuclear tests, which generated film footage of the ominous mushroom clouds raising far above the earth, was the best way to dent the appeal of the CND, and in this the Partial Nuclear Ban Treaty of 1963 was successful.[98]

Wind of Change

Macmillan's first government had seen the first phase of the sub-Saharan African independence movement, which accelerated under his second government.[99] The most problematic of the colonies was the Central African Federation, which had united Northern Rhodesia, Southern Rhodesia and Nyasaland together in 1953 largely out of the fear that the white population of Southern Rhodesia (modern Zimbabwe) might want to join South Africa, which had since 1948 had been led by Afrikaner nationalists distinctly unfriendly to Britain.[100] Though the Central African Federation had been presented as a multi-racial attempt to develop the region, the federation had been unstable right from the start with the black population charging that the whites had been given a privileged position.[100]

Macmillan felt that if the costs of holding onto a particular territory outweighed the benefits then it should be dispensed with. During the Kenyan Emergency, the British authorities tried to protect the Kikuyu population from the Mau Mau guerrillas (who called themselves the "Land and Freedom Army") by interning the Kikuyu in camps. A scandal erupted when the guards at the Hola camp publicly beat 11 prisoners to death on 3 March 1959, which attracted much adverse publicity as the news filtered out from Kenya to the United Kingdom.[100] Many in the British media compared the living conditions in the Kenyan camps to the concentration camps of Nazi Germany, saying that the people in the camps were emaciated and sickly. The report of the Devlin Commission in July 1959 concerning the suppression of demonstrators in Nyasaland (modern-day Malawi) called Nyasaland "a police state".[100] In the aftermath of criticism about colonial policies in Kenya and Nyasland, Macmillan from 1959 onward started to see the African colonies as a liability, arguing at cabinet meetings that the level of force required to hang onto them would result in more domestic criticism, international opprobrium, costly wars, and would allow the Soviet Union to establish influence in the Third World by supporting self-styled "liberation" movements that would just make things worse.[100] After securing a third term for the Conservatives in 1959 he appointed Iain Macleod as Colonial Secretary. Macleod greatly accelerated decolonisation and by the time he was moved to Conservative Party chairman and Leader of the Commons in 1961 he had made the decision to give independence to Nigeria, Tanganyika, Kenya, Nyasaland (as Malawi) and Northern Rhodesia (as Zambia).[101] Macmillan embarked on his "Wind of Change" tour of Africa, starting in Ghana on 6 January 1960. He made the famous 'wind of change' speech in Cape Town on 3 February 1960.[102] It is considered a landmark in the process of decolonisation.

Nigeria, the Southern Cameroons and British Somaliland were granted independence in 1960, Sierra Leone and Tanganyika in 1961, Trinidad and Tobago and Uganda in 1962, and Kenya in 1963. Zanzibar merged with Tanganyika to form Tanzania in 1963. All remained within the Commonwealth except British Somaliland, which merged with Italian Somaliland to form Somalia.

Macmillan's policy overrode the hostility of white minorities and the Conservative Monday Club. South Africa left the multiracial Commonwealth in 1961 and Macmillan acquiesced to the dissolution of the Central African Federation by the end of 1963.

In Southeast Asia, Malaya (which had gained independence on its own in 1957), Sabah (British North Borneo), Sarawak and Singapore formed a new independent nation of Malaysia in 1963. Because Singapore with its ethnic Chinese majority was the largest and wealthiest city in the region, Macmillan was afraid that a federation of Malaya and Singapore together would result in a Chinese majority state, and insisted on including Sarawak and British North Borneo into the federation of Malaysia to ensure the new state was a Malay majority state.[103] During the Malaya Emergency, the majority of the Communist guerrillas were ethnic Chinese, and British policies tended to favour the Muslim Malays whose willingness to follow their sultans and imams made them more anti-communist. Southeast Asia was a region where racial-ethno-religious politics predominated, and the substantial Chinese minorities in the region were widely disliked on the account of their greater economic success.[104] Macmillan wanted Britain to retain military bases in the new state of Malaysia to ensure that Britain was a military power in Asia and thus he wanted the new state of Malaysia to have a pro-Western government.[103] This aim was best achieved by having the same Malay elite who had worked with the British colonial authorities serve as the new elite in Malaysia, hence Macmillan's desire to have a Malay majority who would vote for Malay politicians.[103] Macmillan especially wanted to keep the British base at Singapore, which he like other prime ministers saw as the linchpin of British power in Asia.[105]

The Indonesian president Sukarno strongly objected to the new federation.[106] On 8 December 1962, Indonesia sponsored a rebellion in the British protectorate of Brunei, leading to Macmillan to dispatch Gurkhas to put down the rebellion against the sultan.[107] In January 1963 Sukarno started a policy of konfrontasi ("confrontation") with Britain.[105] Macmillan detested Sukarno, partly because he had been a Japanese collaborator in World War Two, and partly because of his fondness for elaborate uniforms despite never having personally fought in a war offended the World War I veteran Macmillan, who had a strong contempt for any man who had not seen combat.[108] In his diary, Macmillan called Sukarno "a cross between Liberace and Little Lord Fauntleroy".[109] Macmillan felt that giving in to Sukarno's demands would be "appeasement" and clashed with Kennedy over the issue.[108] Sukarno was the leader of the most populous nation in Southeast Asia and though officially neutral in the Cold War, tended to take anti-Western positions, and Kennedy favoured accommodating him to bring him closer to the West; for example, supporting Indonesia's claim to Dutch New Guinea even through the Netherlands was a NATO ally.[108] Macmillan feared the expenses of an all-out war with Indonesia, but also felt to give in to Sukarno would damage British prestige, writing on 5 August 1963 that Britain's position in Asia would be "untenable" if Sukarno were to triumph over Britain in the same manner he had over the Dutch in New Guinea.[110] To help reduce the expenses of the war, Macmillan appealed to the Australian Prime Minister Sir Robert Menzies to send troops to defend Malaysia. On 25 September 1963, Sukarno announced in a speech that Indonesia would "ganyang Malaysia" ("gobble Malaysia raw") and on the same day a mob burned down the British embassy in Jakarta.[105] The result was the Indonesian Confrontation, an undeclared war between Britain vs. Indonesia that began in 1963 and continued to 1966.[111]

The speedy transfer of power maintained the goodwill of the new nations, but critics contended it was premature. In justification Macmillan quoted Lord Macaulay in 1851:

Many politicians of our time are in the habit of laying it down as a self-evident proposition that no people ought to be free until they are fit to use their freedom. The maxim is worthy of the fool in the old story, who resolved not to go into the water until he had learnt to swim. If men are to wait for liberty until they become wise and good in slavery, they may indeed wait for ever.[112]

Skybolt crisis

Macmillan cancelled the Blue Streak ballistic missile in April 1960 over concerns about its vulnerability to a pre-emptive attack, but continued with the development of the air-launched Blue Steel stand-off missile, which was about to enter trials. For the replacement for Blue Steel he opted for Britain to join the American Skybolt missile project. From the same year Macmillan permitted the US Navy to station Polaris submarines at Holy Loch, Scotland, as a replacement for Thor. When Skybolt was unilaterally cancelled by US Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, Macmillan negotiated with President Kennedy the purchase of Polaris missiles under the Nassau agreement in December 1962.[بحاجة لمصدر]

Europe

Macmillan worked with states outside the European Communities (EC) to form the European Free Trade Association (EFTA), which from 3 May 1960 established a free-trade area. As the EC proved to be an economic success, membership of the EC started to look more attractive compared to the EFTA.[113] A report from Sir Frank Lee of the Treasury in April 1960 predicated that the three major power blocs in the decades to come would be those headed by the United States, the Soviet Union and the EC, and argued to avoid isolation Britain would to have decisively associate itself with one of the power blocs.[113] Macmillan wrote in his diary about his decision to apply to join the EC: "Shall we be caught between a hostile (or at least less and less friendly) America and a boastful, powerful 'Empire of Charlemagne'-now under French, but later bound to come under German control?...It's a grim choice".[113]

Through Macmillan had decided upon joining the EC in 1960, he waited until July 1961 to formally make the application, for he feared the reaction of the Conservative Party backbenchers, the farmers' lobby and the populist newspaper chain owned by the right-wing Canadian millionaire Lord Beaverbrook, who saw Britain joining the EC as a betrayal of the British empire.[113] As expected, the Beaverbrook newspapers whose readers tended to vote Conservative offered up ferocious criticism of Macmillan's application to join the EC, accusing him of betrayal. Negotiations to join the EC were complicated by Macmillan's desire to allow Britain to continue its traditional policy of importing food from the Commonwealth nations of Australia, New Zealand and Canada, which led the EC nations, especially France, to accuse Britain of negotiating in bad faith.[113]

Macmillan also saw the value of rapprochement with the EC, to which his government sought belated entry, but Britain's application was vetoed by French president Charles de Gaulle on 29 January 1963. De Gaulle was always strongly opposed to British entry for many reasons. He sensed the British were inevitably closely linked to the Americans. He saw the European Communities as a continental arrangement primarily between France and Germany, and felt that if Britain joined, France's role would diminish.[114][115]

Partial Test Ban Treaty (1963)

Macmillan's previous attempt to create an agreement at the May 1960 summit in Paris had collapsed due to the 1960 U-2 incident. He was a force in the negotiations leading to the signing of the 1963 Partial Test Ban Treaty by the United Kingdom, the United States and the Soviet Union. He sent Lord Hailsham to negotiate the Test Ban Treaty, a sign that he was grooming him as a potential successor.[116]

President Kennedy visited Macmillan's country home, Birch Grove, on 29–30 June 1963, for talks about the planned Multilateral Force. They never met again, and this was to be Kennedy's last visit to the UK. He was assassinated in November, shortly after the end of Macmillan's premiership.[117]

End of premiership

By the early 1960s, many were starting to find Macmillan's courtly and urbane Edwardian manners anachronistic, and satirical journals such as Private Eye and the television show That Was the Week That Was mercilessly mocked him as a doddering, clueless leader.[118] Macmillan's handling of the Vassall affair – in which an Admiralty clerk, John Vassall, was convicted in October 1962 of passing secrets to the Soviet Union – undermined his "Super-Mac" reputation for competence.[118] D. R. Thorpe writes that from January 1963 "Macmillan's strategy lay in ruins", leaving him looking for a "graceful exit". The Vassall affair turned the press against him.[119] In the same month, opposition leader Hugh Gaitskell died suddenly at the age of 56. With a general election due before the end of the following year, Gaitskell's death threw the future of British politics into fresh doubt.[120] The following month Harold Wilson was elected as the new Labour leader, and he proved to be a popular choice with the public.[121]

فضيحة پروفومو

فضيحة پروفومو في ربيع وصيف 1963 ألحقت ضرراً بالغاً بمصداقية حكومة مكميلان. وقد نجا في اقتراع برلماني بالثقة بأغلبية 69، وهو ما يقل بصوت عن الحد المطلوب للبقاء، وحين خرج لغرفة التدخين لم يلحق به سوى ابنه وزوج ابنته، ولا أحد من وزارته. إلا أن البرلمان لم يطالبه بالاستقالة، خاصة بعد موجة التأييد التي حصل عليها من المحافظين في أرجاء البلاد.

The Profumo affair of 1963 permanently damaged the credibility of Macmillan's government. The revelation of the affair between John Profumo (Secretary of State for War) and an alleged call-girl, Christine Keeler, who was simultaneously sleeping with the Soviet naval attache Captain Yevgeny Ivanov made it appear that Macmillan had lost control of his government and of events in general.[122] In the ensuing Parliamentary debate he was seen as a pathetic figure, while Nigel Birch declared, in the words of Browning on Wordsworth, that it would be "Never glad confident morning again!".[123] On 17 June 1963, he survived a Parliamentary vote with a majority of 69,[124] one fewer than had been thought necessary for his survival, and was afterwards joined in the smoking room only by his son and son-in-law, not by any Cabinet minister. However, Butler and Reginald Maudling (who was very popular with backbench MPs at that time) declined to push for his resignation, especially after a tide of support from Conservative activists around the country. Many of the salacious revelations about the sex lives of "Establishment" figures during the Profumo affair damaged the image of "the Establishment" that Macmillan was seen as a part of, giving him the image by 1963 of a "failing representative of a decadent elite".[122]

"ليلة السكاكين الكبيرة"

دعا انخفاض الشعبية العامة لحكومة مكميلان عام 1962 إلى إقصاء ستة وزراء دفعة واحدة، وهو حدث أصبح يعرف بعبارة "ليلة السكاكين الكبيرة". وقع مكميلان أسير المرض عام 1963، وقدم استقالته نظرا لاعتقاده بأن حالته الصحية كانت أسوأ مما كانت فعليا.

وفي عام 1964 تقاعد من عضويته في مجلس العموم ورفض قبول لقب النبلاء. عوضا عن ذلك بدأ يكتب مذكراته، وعمل في دار النشر، وشغل منصب الرئيس الأعلى لجامعة أكسفورد.

عاد مرة أخرى لعضوية البرلمان عام 1984 كأحد النبلاء بالوراثة. وتوفي عام 1986 عن عمر يناهز 92 عاما - وهو أطول عمر عاشه رئيس وزراء لحين وفاة لورد كالاهان عام 2005. كانت آخر كلماته "أعتقد بأنني سوف أخلد إلى النوم الآن".

من أشهر مقولاته"رياح التغيير تهبُّ عبر هذه القارة، وهذا النمو من الوعي الوطني هو حقيقة سياسية، سواء أعجبنا ذلك أم لم يعجبنا" (في كلمة ألقاها أمام البرلمان في جنوب أفريقيا)

هل تعلم؟ من مساهماته التي حُفِرت بالذاكرة بعد تقاعده تشبيهه سياسة التخصيص التي اتبعتها مارگريت ثاتشر بـ"بيع الأواني الفضية التي تعود للعائلة".

خلافته

While recovering in hospital, Macmillan wrote a memorandum (dated 14 October) recommending the process by which "soundings" would be taken of party opinion to select his successor, which was accepted by the Cabinet on 15 October. This time backbench MPs and junior ministers were to be asked their opinion, rather than just the Cabinet as in 1957, and efforts would be made to sample opinion amongst peers and constituency activists.[125]

Enoch Powell claimed that it was wrong of Macmillan to seek to monopolise the advice given to the Queen in this way. In fact, this was done at the Palace's request, so that the Queen was not being seen to be involved in politics as had happened in January 1957, and had been decided as far back as June when it had looked as though the government might fall over the Profumo scandal. Ben Pimlott later described this as the "biggest political misjudgement of her reign".[126][127]

Macmillan was succeeded by Foreign Secretary Alec Douglas-Home in a controversial move; it was alleged that Macmillan had pulled strings and utilised the party's grandees, nicknamed "The Magic Circle", who had slanted their "soundings" of opinion among MPs and Cabinet Ministers to ensure that Butler was (once again) not chosen.[128]

He finally resigned, receiving the Queen from his hospital bed, on 18 October 1963, after nearly seven years as prime minister. He felt privately that he was being hounded from office by a backbench minority:

Some few will be content with the success they have had in the assassination of their leader and will not care very much who the successor is. ... They are a band that in the end does not amount to more than 15 or 20 at the most.[129]

الزوجة

ليدي كافيندش - وهي أم لأربعة من الأبناء - لديها فراسة بالحكم على الناس، وقد وصفتها ابنة أخيها بأنها "لا تحمل أي نوع من التكبُّر على الآخرين". كانت امرأة جامحة وعاطفية في شبابها، ونمت الجاذبية لديها في سن مبكرة، وكان لها حضور قوي وفهم بديهي للأمور السياسية.

قامت بالعديد من الأعمال الخيرية - والتي حصلت على تكريم بسببها - وكانت تدعم طموحات زوجها. وقيل بأنها كانت "تحب الأطفال بشدة واستطاعت أن تنسجم تماما معهم".[130]

المنزل رقم 10 بحد ذاته لم يكن عائقا أمامها - فحيث أن والدها كان برتبه ديوك كانت معتادة على الاهتمام بالمنازل الكبيرة - واعتبرت هذا المنزل بكل بساطة على أنه "مسكن بالمدينة". عند وفاتها كان زوجها شديد الحزن لدرجة أنه لا يمكن مواساته. "لقد ملأت عليّ حياتي"، كما قال، "وفكرت بكل ما قدمته لها."

قراءات إضافية

- Macmillan A Publishing Tradition by Elizabeth James 2002 ISBN 0-333-73517-X

- Britanica Online about Harold Macmillan

ملاحظات

المصادر

- Theatre Record (1997 for Hugh Whitemore's A Letter of Resignation; 2008 for Howard Brenton's Never So Good)

- ^ When Fisher resigned in 1961

- ^ "Harold Macmillan Dies at 92". The New York Times. 30 December 1986. Archived from the original on 29 June 2021. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ^ Middleton 1997.

- ^ Middleton 1997, p. 422.

- ^ Hennessy 2006, pp. 533–34.

- ^ Lamb 1995, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Leitch, David (8 December 1996), "The spy who rocked a world of privilege", The Independent (London), https://www.independent.co.uk/opinion/the-spy-who-rocked-a-world-of-privilege-1313565.html

- ^ هارولد ماكميلان

- ^ Edmund Dell, The Chancellors: A History of the Chancellors of the Exchequer, 1945–90 (1997) pp. 207–222, covers his term as Chancellor.

- ^ Campbell 2010, pp. 261–262, 264.

- ^ Campbell 2010, pp. 264–265.

- ^ 18 April 1956: Macmillan unveils premium bond scheme , BBC News, 'On This Day 1950–2005'.

- ^ Horne 2008, p. 383.

- ^ John Major (1999). John Major: The Autobiography. HarperCollins. p. 26.

- ^ Harold Macmillan; Unflappable master of the middle way Archived 19 فبراير 2014 at the Wayback Machine, obituary in The Guardian, by Vernon Bogdanor; 30 December 1986.

- ^ Horne 2008, p. 441.

- ^ Bertjan Verbeek, Decision-making in Great Britain during the Suez crisis (2003) p. 95.

- ^ Campbell 2010, p. 265.

- ^ Beckett 2006, p. 74.

- ^ Toye, Richard Churchill's Empire: The World That Made Him and the World He Made (2010) p. 304.

- ^ Beckett 2006, pp. 73–74.

- ^ أ ب Diane B. Kunz, The Economic Diplomacy of the Suez Crisis (1991) pp. 130–40.

- ^ Howard 1987, p. 237.

- ^ Williams 2010, p. 267.

- ^ Thorpe 2010, p. 356.

- ^ Howard 1987, p. 239.

- ^ Howard 1987, p. 242.

- ^ Thorpe 2010, pp. 352–53.

- ^ Howard 1987, pp. 240–241.

- ^ Thorpe 2010, pp. 353–354.

- ^ Campbell 2010, p. 269.

- ^ Howard 1987, p. 244.

- ^ Thorpe 2010, p. 358.

- ^ Beckett 2006, pp. 77–78.

- ^ Thorpe 2010, pp. 361–362.

- ^ Harold Macmillan, The Macmillan Diaries, The Cabinet Years, 1950–1957, ed. Peter Catterall (London: Macmillan, 2003).

- ^ Horne 1989, pp. 5, 13.

- ^ David Butler, Twentieth Century British Political Facts 1900–2000, Macmillan, 8th edition, 2000.

- ^ Gyles Brandreth. Brief encounters: meetings with remarkable people (2001) p. 214.

- ^ أ ب ت Goodlad & Pearce, 2013 p. 169.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د Goodlad & Pearce, 2013 p. 170.

- ^ Colin Seymour-Ure, Prime Ministers and the Media: issues of power and control (2003) p. 261.

- ^ Edmund Dell, The Chancellors: A History of the Chancellors of the Exchequer, 1945–90 (1997) pp. 223–303.

- ^ أ ب Thorpe 2010, pp. 401–407.

- ^ Thorpe 2010, p. 407.

- ^ David Kynaston, Till Time's Last Stand: A History of The Bank of England, 1694–2013, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2017, pp. 434–435.

- ^ OCR A Level History B: The End of Consensus: Britain 1945–90 by Pearson Education.

- ^ Davey Smith, George; Dorling, Daniel; Shaw, Mary (11 July 2001). Poverty, Inequality and Health in Britain, 1800–2000: A Reader. Policy Press. ISBN 9781861342119. Archived from the original on 8 November 2021. Retrieved 18 October 2013.

- ^ Micklitz, H. W. (1 November 2011). The Many Concepts of Social Justice in European Private Law. Edward Elgar. ISBN 9780857935892. Retrieved 18 October 2013.

- ^ Spicker, Paul (2011). How Social Security Works: An Introduction to Benefits in Britain. Policy Press. ISBN 9781847428103. Archived from the original on 8 November 2021. Retrieved 18 October 2013.

- ^ Mastering Modern World History by Norman Lowe.

- ^ Fisher 1982, p. 214.

- ^ Fisher 1982, p. 193.

- ^ Horne, Macmillan, Volume II, pp. 94–95.

- ^ Horne, Macmillan, Volume II, p. 419.

- ^ Onslow, Sue (13 July 2015). "The Commonwealth and the Cold War, Neutralism, and Non-Alignment". The International History Review. 37 (5): 1059–1082. doi:10.1080/07075332.2015.1053965. S2CID 154044321. Retrieved 14 March 2023.

- ^ Nick Rufford, 'A-bomb links kept secret from Queen', Sunday Times (3 January 1988).

- ^ 'Windscale: Britain's Biggest Nuclear Disaster', broadcast on Monday, 8 October 2007, at 2100 BST on BBC Two.

- ^ Paddy Shennan, 'Britain's Biggest Nuclear Disaster', Liverpool Echo (13 October 2007), p. 26.

- ^ John Hunt. 'Cabinet Papers For 1957: Windscale Fire Danger Disclosed', Financial Times (2 January 1988).

- ^ David Walker, 'Focus on 1957: Macmillan ordered Windscale censorship', The Times (1 January 1988).

- ^ Jean McSorley, 'Contaminated evidence: The secrecy and political cover-ups that followed the fire in a British nuclear reactor 50 years ago still resonate in public concerns', The Guardian (10 October 2007), p. 8.

- ^ John Gray, 'Accident disclosures bring calls for review of U.K. secrecy laws', Globe and Mail (Toronto, 4 January 1988).

- ^ Richard Gott, 'The Evolution of the Independent British Deterrent', International Affairs, 39/2 (April 1963), p. 246.

- ^ Gott, 'Independent British Deterrent', p. 247.

- ^ The Times (4 July US Navy).

- ^ Ashton 2005, p. 699.

- ^ Ashton 2005, pp. 699–700.

- ^ Ashton 2005, p. 700.

- ^ Ashton 2005, p. 702.

- ^ Ashton 2005, p. 703.

- ^ Harold Macmillan, Speech in Bedford, 20 July 1957, BBC News, 20 July 1974, https://news.bbc.co.uk/onthisday/hi/dates/stories/july/20/newsid_3728000/3728225.stm, retrieved on 31 January 2010

- ^ Lamb 1995, p. 62.

- ^ "1959: Macmillan wins Tory hat trick". 5 April 2005. Archived from the original on 22 April 2009 – via news.bbc.co.uk.

- ^ أ ب "Cabinet Papers – Strained consensus and Labour". Nationalarchives.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 21 October 2017.

- ^ Thorpe 2010, p. 518.

- ^ Thorpe 2010, p. 520.

- ^ Thorpe 2010, p. 524.

- ^ Thorpe 2010, p. 525.

- ^ Garry Keenor. "The Reshaping of British Railways – Part 1: Report". The Railways Archive. Archived from the original on 19 October 2010. Retrieved 25 July 2010.

- ^ Campbell 2010, p. 275.

- ^ Ashton 2005, pp. 703–704.

- ^ أ ب Ashton 2005, p. 704.

- ^ أ ب Ashton 2005, p. 705.

- ^ أ ب Ashton 2005, p. 707.

- ^ Ashton 2005, pp. 708–709.

- ^ أ ب Ashton 2005, p. 709.

- ^ أ ب Busch 2003, p. 20.

- ^ Ashton 2005, pp. 709–710.

- ^ Busch 2003, p. 22.

- ^ Busch 2003, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Ashton 2005, p. 710.

- ^ Ashton 2005, p. 712.

- ^ Christopher Sandford, Harold and Jack: The Remarkable Friendship of Prime Minister Macmillan and President Kennedy (2014) pp. 212–213.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Ashton 2005, p. 719.

- ^ أ ب Ashton 2005, p. 713.

- ^ أ ب Ashton 2005, p. 714.

- ^ أ ب Wright 1999, p. 10.

- ^ Larry Butler and Sarah Stockwell, eds. The wind of change: Harold Macmillan and British decolonization (Springer, 2013).

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Goodlad & Pearce, 2013 p. 176.

- ^ Toye, Richard Churchill's Empire: The World That Made Him and the World He Made (2010) p. 306.

- ^ "Harold Macmillan begins his "winds of change" tour of Africa". South Africa History Online. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015.

- ^ أ ب ت Subritzy 1999, p. 181.

- ^ Subritzy 1999, p. 180.

- ^ أ ب ت Busch 2003, p. 174.

- ^ Subritzy 1999, p. 187-190.

- ^ Busch 2003, p. 176.

- ^ أ ب ت Subritzy 1999, p. 190.

- ^ Subritzy 1999, p. 189.

- ^ Busch 2003, p. 182-183.

- ^ Subritzy 1999, pp. 189–190.

- ^ Fisher 1982, p. 230.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Goodlad & Pearce, 2013 p. 178.

- ^ George Wilkes, Britain's failure to enter the European community 1961–63: the enlargement negotiations and crises in European, Atlantic and Commonwealth relations (1997) [1] Archived 26 مايو 2016 at the Wayback Machine p. 63 online.

- ^ Lamb 1995, pp. 164–65, chapters 14 and 15.

- ^ Thorpe 2010, pp. 551–552.

- ^ Thorpe 2010, pp. 504–05.

- ^ أ ب Goodlad & Pearce, 2013 p. 179.

- ^ Thorpe 2010, p. 613.

- ^ "1963: Labour leader Hugh Gaitskell dies". BBC News. 21 October 1963. Archived from the original on 15 July 2015.

- ^ "1963: a year to remember". BBC Democracy Live. 28 March 2013. Archived from the original on 26 April 2016.

- ^ أ ب Goodlad & Pearce, 2013 p. 180.

- ^ SECURITY (MR. PROFUMO'S RESIGNATION) (Hansard, 17 June 1963)

- ^ "SECURITY (MR. PROFUMO'S RESIGNATION)". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 17 June 1963. Archived from the original on 7 May 2016.

- ^ Thorpe 2010, pp. 566–567.

- ^ Thorpe 2010, pp. 569–570.

- ^ Pimlott, Ben (1997). The Queen : A Biography of Elizabeth II. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 335. ISBN 047119431X.

- ^ the "soundings" and the accompanying political intrigues are discussed in detail in Rab Butler's biography.

- ^ Anthony Bevins, 'How Supermac Was "Hounded Out of Office" by Band of 20 Opponents', The Observer (1 January 1995), p. 1.

- ^ ماكميلان

وصلات خارجية

- BBC Harold Macmillan obituary

- Some Harold Macmillan quotes

- President of the friends of Roquetaillade association [2]

- 8 June 1958 speech on "Interdependence" at DePauw University

- More about Harold Macmillan on the Downing Street website

- RootsAndLeaves.com, Cavendish family genealogy

- Bodleian Library Suez Crisis Fiftieth Anniversary Exhibition

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- مقالات بالمعرفة بحاجة لذكر رقم الصفحة بالمصدر from October 2022

- Articles with unsourced statements from February 2018

- رءؤساء وزراء المملكة المتحدة

- زعماء حزب المحافظين البريطانيين

- وزراء خزانة المملكة المتحدة

- وزراء خارجية بريطانيين

- أعضاء برلمان عن حزب المحافظين (المملكة المتحدة)

- قادة الحرب الباردة

- أعضاء برلمان المملكة المتحدة 1924-1929

- أعضاء برلمان المملكة المتحدة 1931-1935

- أعضاء برلمان المملكة المتحدة 1935-1945

- أعضاء برلمان المملكة المتحدة 1945-1950

- أعضاء برلمان المملكة المتحدة 1950-1951

- أعضاء برلمان المملكة المتحدة 1951-1955

- أعضاء برلمان المملكة المتحدة 1955-1959

- أعضاء برلمان المملكة المتحدة 1959-1964

- أعضاء مجلس الخاصة في المملكة المتحدة

- أعضاء برلمان المملكة المتحدة عن دوائر إنگليزية

- Grenadier Guards officers

- أفراد الجيش البريطاني في الحرب العالمية الأولى

- Old Etonians

- خريجو جامعة أكسفورد

- أشخاص مرتبطون بجامعة أكسفورد

- مستشارو جامعة أكسفورد

- أعضاء مرتبة الاستحقاق

- أشخاص من بريكستون

- Earls in the Peerage of the United Kingdom

- إنگليز من أصل اسكتلندي

- أنگليكان إنگليز

- مواليد 1894

- وفيات 1986